Pearlcasts

As we review 2025, the temptation is to look for neat summaries and settled conclusions.

Go to Pearlcasts

7 February 2026

Isaac Herzog is accused of inciting genocide in Gaza. He shouldn’t be welcomed to Australia

Writing in the Guardian on Thursday UN Commissioner Chris Sidoti laid out the reasons Isaac Herzog should not be welcome in Australia, and urged the Prime Minister to correct his terrible mistake in inviting him.

7 February 2026

Message from the Editor

The debate over the visit of the Israeli President has occupied much space in P&I this week, and for good reason.

7 February 2026

Australia unlikely to follow US downgrade on China threat

The US National Defense Strategy signals a softer, more pragmatic approach to China. Australia’s silence on the shift exposes how detached its defence posture has become from both reality and its own national interests.

7 February 2026

Billionaire Bezos guts Washington Post

The gutting of the Washington Post has reignited a deeper question about who controls the media – and whether billionaire ownership is compatible with a free press.

7 February 2026

Australian doctors protest Israel’s destruction of health rights in Gaza

Israel’s deregistration of international health providers in Gaza makes legally mandated care increasingly impossible, raising serious questions about compliance with international law.

7 February 2026

Herzog’s visit exposes Australia’s legal weakness on human rights

As Israel’s president visits Australia, debates over protest, terrorism and antisemitism expose a significant problem: Australia lacks a coherent human rights framework.

7 February 2026

Inside Indonesia’s Board of Peace diplomacy on Palestine

Indonesia’s decision to join the Board of Peace places it inside a US-dominated body whose approach to Gaza risks prioritising reconstruction over sovereignty, rights and political legitimacy.

6 February 2026

Don't mention the war

Australia is struggling to respond proportionately to violence, fear and political pressure in the wake of the Bondi attacks, October 7 and Israel’s war in Gaza. The result has been a contraction of democratic debate, heavy-handed political responses and an unwillingness to confront the scale of civilian suffering now unfolding in Gaza.

6 February 2026

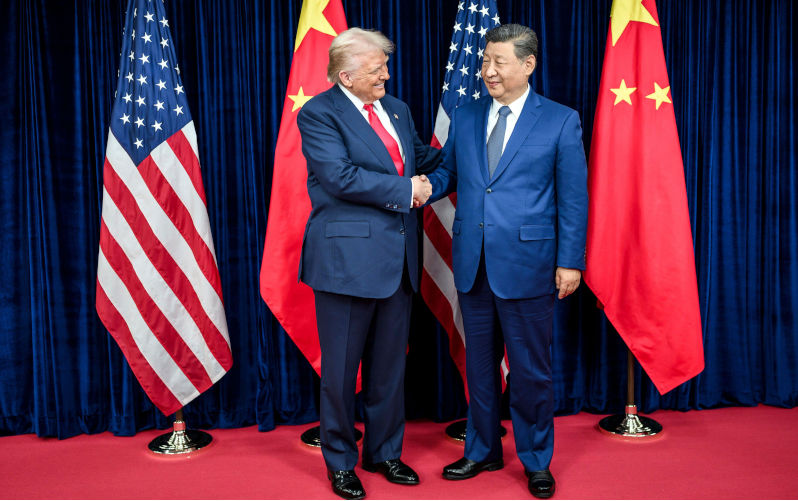

America’s bad emperor problem

History offers a warning about unchecked power. As Donald Trump reshapes US foreign policy, the risks of personal rule and predatory hegemony are becoming harder to ignore.

6 February 2026

The China AI panic misses what history keeps teaching us

Warnings that China must be cut off from advanced AI chips echo a familiar pattern. History suggests technology bans rarely slow China down – and often do the opposite.

6 February 2026

Why is the Australian government hosting the President of Israel?

As President Isaac Herzog prepares for an official visit, Australia faces serious questions about international law, diplomatic process, and the values it claims to uphold.

Read our series

Latest on Palestine and Israel

7 February 2026

Isaac Herzog is accused of inciting genocide in Gaza. He shouldn’t be welcomed to Australia

Writing in the Guardian on Thursday UN Commissioner Chris Sidoti laid out the reasons Isaac Herzog should not be welcome in Australia, and urged the Prime Minister to correct his terrible mistake in inviting him.

7 February 2026

Australian doctors protest Israel’s destruction of health rights in Gaza

Israel’s deregistration of international health providers in Gaza makes legally mandated care increasingly impossible, raising serious questions about compliance with international law.

6 February 2026

Don't mention the war

Australia is struggling to respond proportionately to violence, fear and political pressure in the wake of the Bondi attacks, October 7 and Israel’s war in Gaza. The result has been a contraction of democratic debate, heavy-handed political responses and an unwillingness to confront the scale of civilian suffering now unfolding in Gaza.

5 February 2026

Like a gambler who lost his fortune, Israel wants another war

Despite a declared ceasefire and the return of hostages, large-scale killing has continued in Gaza. The war has become self-perpetuating, leaving Israel morally, politically and strategically diminished.

5 February 2026

The meteoric rise of UpScrolled (and the Australian media’s silence about it)

An Australian social media platform surged to millions of users amid global concern over censorship and Gaza. Yet its rise has been largely ignored by Australia’s media.

5 February 2026

Herzog’s visit "a terrible cruelty"

For Palestinian Australians who have lost entire families in Gaza, the decision to welcome Israel’s president to Australia is not diplomatic neutrality but an act of profound cruelty. As deaths continue despite a ceasefire, questions of grief, justice and political accountability can no longer be avoided.

4 February 2026

Allegations, immunity, and a test of character

Australia’s migration law allows entry to be refused on character grounds including genocide, war crimes and incitement. How that discretion is exercised speaks directly to Australia’s commitment to international law.

4 February 2026

Israel and the return of settler politics in a lawless international system

Zionism emerged at the height of European settler colonialism and was realised just as the world turned toward decolonisation. Today, as international law loses force, Israel’s actions are again enabled by the prevailing global order.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

7 February 2026

Australia unlikely to follow US downgrade on China threat

The US National Defense Strategy signals a softer, more pragmatic approach to China. Australia’s silence on the shift exposes how detached its defence posture has become from both reality and its own national interests.

6 February 2026

The China AI panic misses what history keeps teaching us

Warnings that China must be cut off from advanced AI chips echo a familiar pattern. History suggests technology bans rarely slow China down – and often do the opposite.

4 February 2026

China pushes ahead in 2026 as Trump plays catch-up

China entered Donald Trump’s second presidency wary but prepared. Experience has taught Beijing to expect volatility, but also negotiation, shaping a strategy of caution, leverage and long-term planning.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

The propaganda of American might

Ian Bowrey — Hamilton South

Tactical voting by Labor voters

John Small — Marrickville, NSW

But what about Pine Gap?

Penny Lee — Western Australia

Translation problems

Geoff Taylor — Borlu (Perth)