13 May 2025

Politics courting religion: Religion courting politics politics, religion

An open letter to the Coalition leadership There has been a growing trend for Conservative politics in the US and in Australia to double down on support from conservative expressions of Christian religious faith. These religious views are not consistent with the values of most Australians, they are divisive. They do not represent the views of those with faith, like me, who find them at odds with the life and teaching of Jesus.

13 May 2025

Chinese Australians’ rejection of the Liberal Party: Ten moments

The rejection of the Liberal Party by Chinese Australian communities in the election was comprehensive and unambiguous.

13 May 2025

There is no Jewish vote in Australia nor is supporting Israel a vote winner

The election results show that a pro-Israel policy does not garner votes for the Liberal or Labor parties, a trend also evident in the 2022 election.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDF

13 May 2025

Labor stops apologising for its social commitments

Some of the most memorable political speeches made in Australia have been made by politicians who are leaving office.

13 May 2025

Productivity with purpose: Roy Green, structural reform and Australia’s place in the world

Roy Green’s recent article on productivity reform offers one of the most cogent and hopeful visions for Australia’s economic future.

13 May 2025

Trump’s USAID cuts only accelerate the West’s miserly convergence with China

Critics of the Trump administration’s assault on foreign aid warn that it will undermine the United States’ capacity to compete with China.

13 May 2025

Indonesia's old guard wants its old world back

Anthony Albanese’s pilgrimage to Jakarta this week as the new prime minister follows the standard post-election Hi Neighbours goodwill wave. But this time the parades and handshakes may get blurred by heat from Indonesia’s simmering Constitutional crisis.

12 May 2025

Mark Leibler on his lobbying power

In a speech he delivered back in 2018, Mark Leibler lays out how he exerts influence, from trying to block Bob Carr's efforts on recognition of a Palestinian State to watching ABC correspondent Sophie McNeill in order to change her coverage of the Middle East.

12 May 2025

Message from the editor

Welcome to a new week, a new pope, a new cabinet and a new Opposition Leader. And for the first time, there are at least 57% women in the ALP caucus and record numbers of women across the federal Parliament.

12 May 2025

Shell-shocked voters of US allies choose stability over disruption

Rather than left- or right-leaning political parties, citizens in Singapore, Australia and Canada chose steady hands to navigate geopolitical turbulence.

12 May 2025

Can Albanese resist the temptation to fall for Trump’s flattery?

Without wishing to rain on the Australian Labor Party’s victory parade, when our prime minister was congratulated and praised by Donald Trump the day after Labor won the 2025 federal election, alarm bells should have been ringing to alert his advisers.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

12 May 2025

Mark Leibler on his lobbying power

In a speech he delivered back in 2018, Mark Leibler lays out how he exerts influence, from trying to block Bob Carr's efforts on recognition of a Palestinian State to watching ABC correspondent Sophie McNeill in order to change her coverage of the Middle East.

11 May 2025

At the ICJ, only US and Hungary back Israel starving Gaza

Thirty-seven states, the UN and international NGOs all condemned Israel’s denial of aid to the starving people of Gaza at the International Court of Justice in the first week of May.

10 May 2025

'This isn't me': Israeli war and healthcare collapse leave Gaza child unrecognisable

Under a tightening Israeli siege, Palestinian girl Rahaf Ayyad struggles with physical and emotional changes, as her mother fights for answers.

9 May 2025

Aid to Gaza: Moral and political dilemmas for Australia

Amidst preparations for a renewed assault intended to allow permanent Israeli occupation of Gaza, Israel and the United States are also about to establish a mechanism through which humanitarian aid will henceforth be distributed exclusively by private firms protected by the Israeli military.

9 May 2025

Re-elected Albanese Govt must condemn Israel's brutality and cut ties

On 5 May, the Israeli Parliament approved plans to annex and occupy Gaza. These plans have been discussed for months. This is a blatant mission to ethnically cleanse Gaza, advancing Israel’s colonial intentions to take over the territory and rid it of Palestinians.

9 May 2025

Zionist lawfare comes for Australian journalist

The Zionist federation of Australia should be recognised as a duplicitous and malicious actor in Australian society and politics.

8 May 2025

Mainstream media and distorted Palestine reporting

Australia’s mainstream media have ignored and distorted the genocide in Palestine. A recent Australians for Humanity forum, chaired by former SBS newsreader Mary Kostakidis, and featuring Margaret Reynolds, Stuart Rees and Peter Slezak, tackled the issues and discussed what needs to be done.

7 May 2025

Judaism and Zionism are not the same

No doubt about it. We live in a topsy-turvy world. How Kafkaesque can it get, when some of Zionism’s most fervent supporters have been politicians like Scott Morrison, Peter Dutton or — God help us — the Mad King of Mar-a-Lago?

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateLatest on China

13 May 2025

Trump’s USAID cuts only accelerate the West’s miserly convergence with China china, economy, politics, usa

Critics of the Trump administration’s assault on foreign aid warn that it will undermine the United States’ capacity to compete with China.

12 May 2025

Shell-shocked voters of US allies choose stability over disruption

Rather than left- or right-leaning political parties, citizens in Singapore, Australia and Canada chose steady hands to navigate geopolitical turbulence.

10 May 2025

China touts new law as foundation for private sector growth

A week after the passage of a law on China’s private economy, officials said the bill would unleash the potential of the non-state sector.

More from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Bring back the whip

Bob Pearce — Adelaide SA

Labor 2025: purpose or puppetry?

Chris Young — Surrey Hills, Vic

Was it a strategic mistake to sack Husic?

Doug Foskey — Tregeagle

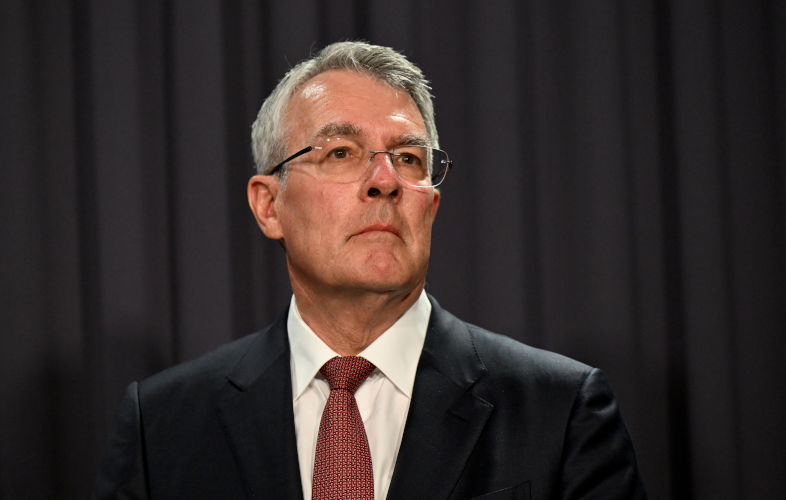

Greg Barns is spot on about Mark Dreyfus

Marion Buchanan — White Gum Valle, WA