2 July 2025

How spending more on defence harms the nation

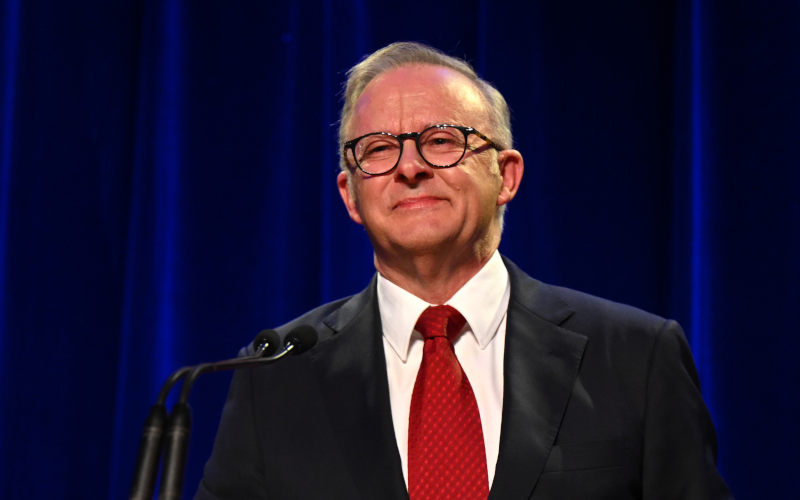

Anthony Albanese is taking a battering from ill-informed commentators for thinking Australia can be defended by spending a little over 2% of GDP on its military forces.

2 July 2025

Gaza’s Hunger Games

Israel is weaponising starvation. The objective is to dismantle all remnants of civil society and reduce Palestinians to herds of desperate scavengers who can be driven from historic Palestine.

2 July 2025

As heatwave grips Europe, coalition says 'no to a climate law for polluters'

Will the European Commission propose a climate law that ends fossil fuel use and reflects the EU's fair share of climate responsibility? Or will it choose political convenience?

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

2 July 2025

Flour instead of homeland: manufacturing the crisis and the end of the Palestinian dream

Since 4:00 p.m. on 14 May 1948, the Palestinian cause has been one of a homeland seized by force, a land torn from its people by Zionism through weapons and terror.

2 July 2025

Southeast Asia needs to ramp up its trade links with Europe

Southeast Asia faces rising US tariffs and pressure to limit Chinese links, prompting a search for stronger European trade ties. While Europe offers promising opportunities, ASEAN must navigate complex bilateral deals that may risk regional cohesion. Closer EU ties can diversify markets and investments, but will not replace China’s role in supply chains. To fully benefit, Southeast Asian nations must drive domestic reforms, enhancing resilience and inclusive growth amid global trade uncertainties.

2 July 2025

Will the 'Mr Magoo Nation' stand up against 'Trumpist' geopolitics?

In the June 7-8 issue of The Australian Greg Sheridan railed against the ‘’crushing waves of [Chinese] military threat” and satirised the Albanese Government’s “pathological passivity” as reminiscent of Peter Seller’s quietly subversive Chauncey Gardner.

2 July 2025

Research misconduct: Strengthening Australia’s research integrity system

A new book, Doctored: Fraud, Arrogance and Tragedy in the Quest to Cure Alzheimer’s by Charles Piller is a deeply dispiriting story. Dispiriting in particular, as it yet again tells a story of harmful unchecked research misconduct.

2 July 2025

Australia’s decision-makers are ignoring climate, hailing coal and impersonating Elvis

You could barely believe that there is a climate crisis going on. In the same week that climate scientists suggested the world will exhaust its remaining carbon budget within two years, carbon bombs are being set off left, right and centre, or allowed through regulatory hurdles on the promise of buying dodgy offsets.

2 July 2025

Courage needs to be shown in politics – Israel is no longer above the law

In the past weeks, an estimated 500 more Gazans have been killed, bombed out of existence by the IDF or killed while queuing for food.

2 July 2025

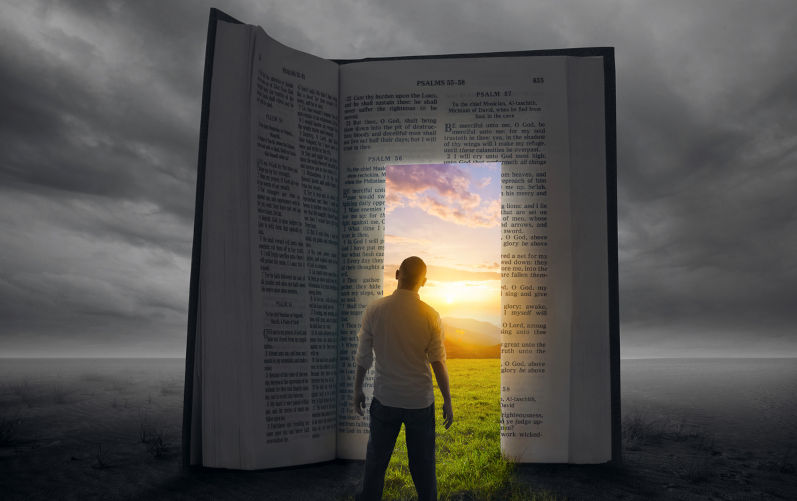

Five books the Bible could do without

When ancient scriptures continue to shape modern ideology and policy, especially where harm is done, it becomes necessary to ask: do all parts of the Bible deserve to be treated as sacred?

1 July 2025

The contemporary world is run by political dinosaurs facing extinction

An aging generation of mostly male leaders is presently occupying the commanding heights of the most powerful states around the world.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

2 July 2025

Gaza’s Hunger Games

Israel is weaponising starvation. The objective is to dismantle all remnants of civil society and reduce Palestinians to herds of desperate scavengers who can be driven from historic Palestine.

2 July 2025

Flour instead of homeland: manufacturing the crisis and the end of the Palestinian dream

Since 4:00 p.m. on 14 May 1948, the Palestinian cause has been one of a homeland seized by force, a land torn from its people by Zionism through weapons and terror.

2 July 2025

Courage needs to be shown in politics – Israel is no longer above the law

In the past weeks, an estimated 500 more Gazans have been killed, bombed out of existence by the IDF or killed while queuing for food.

30 June 2025

Lattouf’s victory, our fight: Standing firm against intimidation

In April 2025, I posted a comment in The Age, sharing how, after 40 years in my Goldstein neighbourhood, I’d never felt unsafe until I was wrongly accused of antisemitism.

29 June 2025

Starvation and profiteering in Gaza (with Francesca Albanese) | The Chris Hedges Report

Francesca Albanese joins Chris Hedges to break down the current starvation campaign in Gaza, and her upcoming report detailing the profiteering corporations capitalising on the erasure of Palestinians.

29 June 2025

Three blows against Zionism in a single day

A court ruling in Australia, an election result in New York and a military setback for Israel, all coming last week, signalled a serious turn of events for Zionism and its supporters, writes Joe Lauria.

28 June 2025

The generational divide in the West over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: from a culture of loyalty to a culture of justice

A deep analysis of the growing generational divide in the West over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

27 June 2025

Don't talk or write about Palestine. It's a career killer

The new McCarthyism sweeps through the university sector at a terrifying pace. At the core is conflation of antisemitism with criticism of Israel, spurred on by the pro-Israel lobby that has convinced or recruited governments and large sections of the media.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

30 June 2025

China is taking Silicon Valley’s market ‘hacks’ to a whole new level

From blitzscaling to leveraging network effects, China is using the same methods to dominate supply chain and disrupt markets.

28 June 2025

No time to dye: ABC’s China bias is licensed to kill credibility

The ABC has long held a reputation as Australia’s sober, publicly-funded bulwark against tabloid sensationalism – the broadcaster you turn to when you want analysis, not alarmism.

28 June 2025

China’s partnership with Muslim world is redrawing global landscape

Once seen as unlikely partners, this axis is now grounded in respect, sovereignty and a shared aspiration for a post-Western world order.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Kelty and Keating’s lasting legacy

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

Thanks, Paul

Bob Pesrce — Adelaide SA

Thank you, Mr Keating

Robyn Dalziell — Sydney

Avoiding the maelstrom of America's death throes

Albert Turley — Doncaster, VIC