13 July 2025

Abandoning our fears: how Australia should respond to US-China regional confrontation

A presentation by Professor Gareth Evans, former Australian foreign minister, to the University of Melbourne Australian Peace and Security Forum Webinar Abandoning our Fears: Finding Peace and Security in our Region, 8 July 2025.

13 July 2025

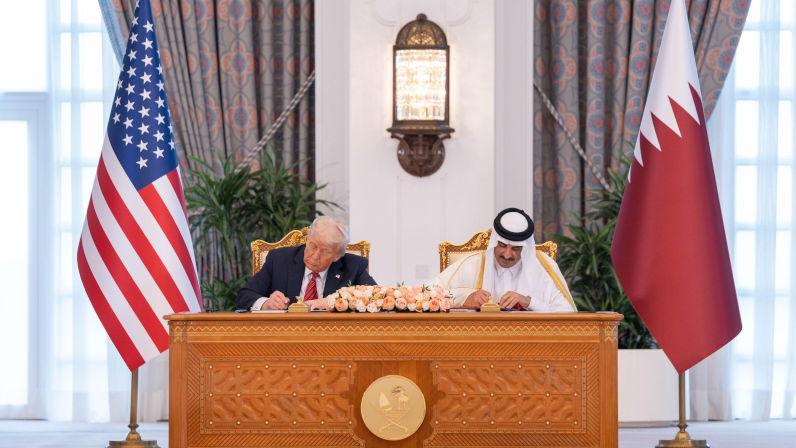

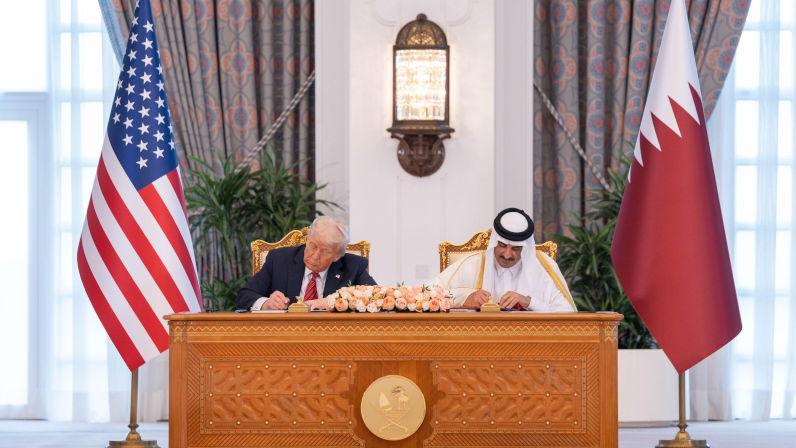

As Trump flip-flops on tariffs, what’s the point of negotiating at all?

Are the tariffs a reality show aimed at Americans, a way to gain the upper hand on China, or just a distraction from sector-specific duties?

13 July 2025

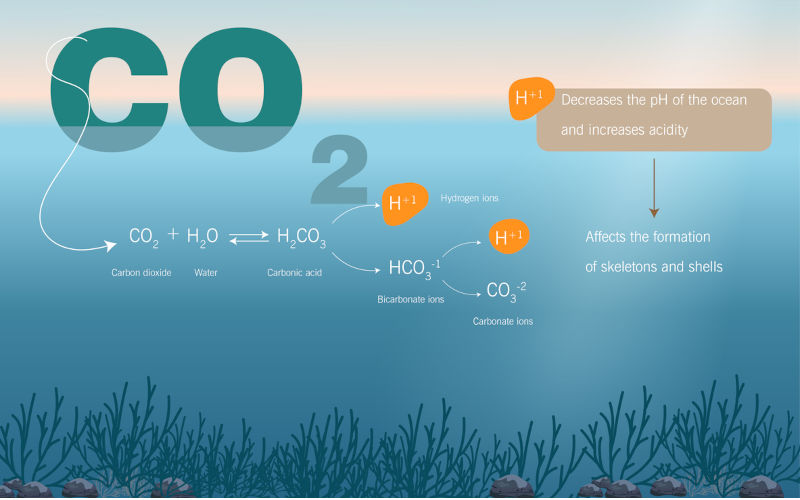

Environment: Ocean acidification has left the safe zone for humans

Seven of the nine planetary boundaries have now been crossed. Civil society calls for major reform of COP meetings. Big banks fund Australian deforestation. China leaving USA behind in the energy transition.

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

13 July 2025

Kostakidis to go before court, after judiciary recognises anti-Zionism is not antisemitism

Mary Kostakidis should hold her head up high right now, because of all the Australian journalists who are honestly calling out the holocaust that Israel is perpetrating against the Palestinians.

12 July 2025

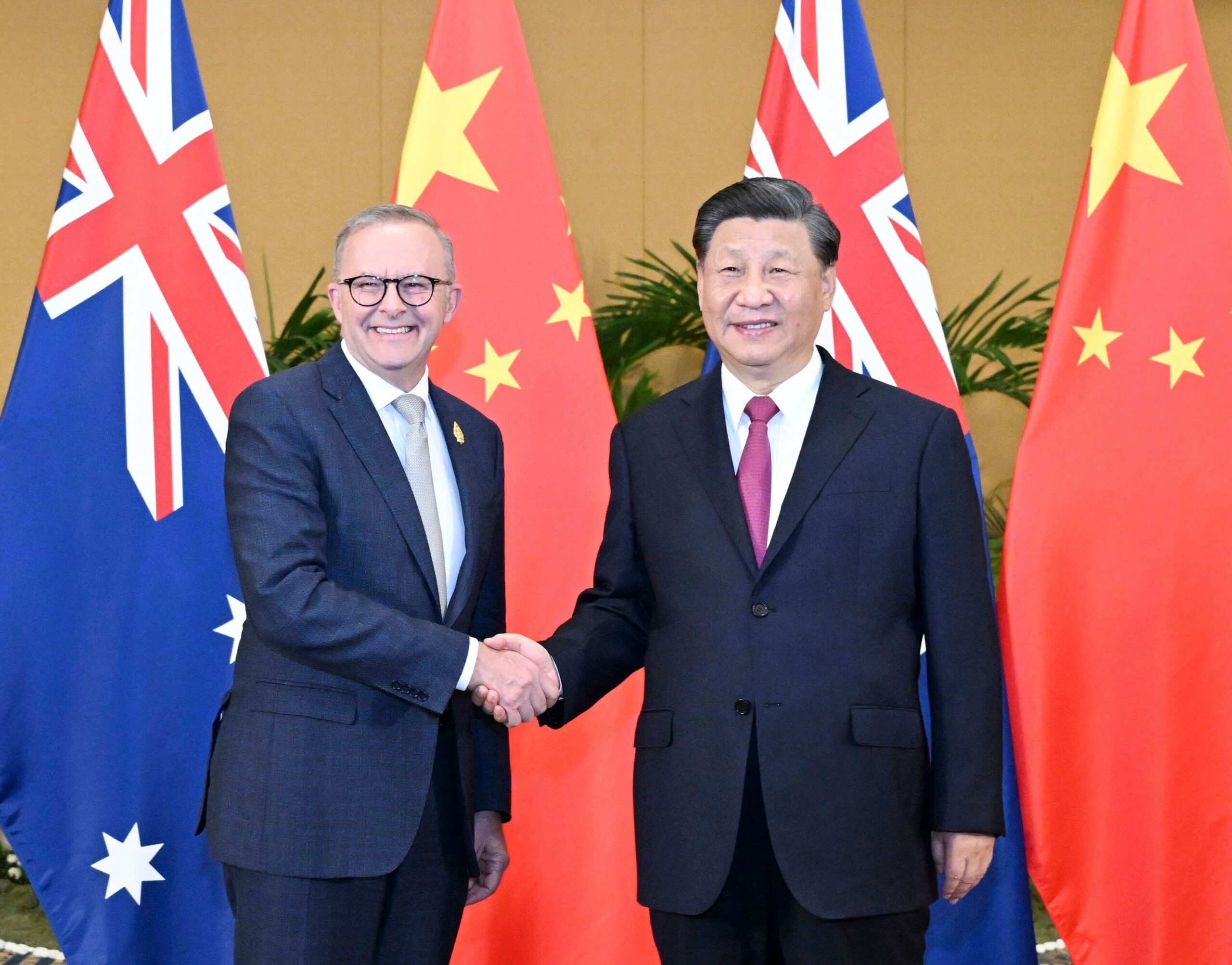

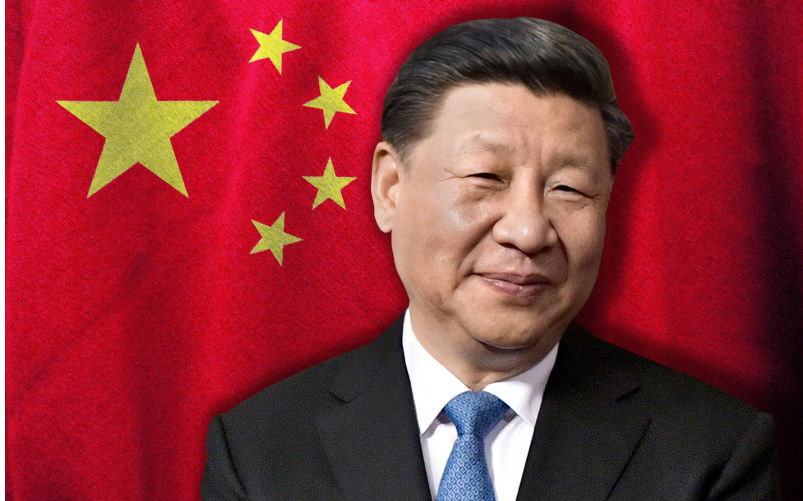

Albanese’s visit to China is a moment for statesmanship

Membership of the Chinese Communist Party has just exceeded 100 million. It has long been the largest political party in world history.

12 July 2025

The Texas flood, Australia and the psychology of evacuation

The Texas flood on the weekend of 4 July has produced a shocking toll – probably well over 200 people dead, including many children.

12 July 2025

Albanese’s China mission – managing a complex relationship in a world of shifting alliances

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese leaves for China on Saturday, confident most Australians back the government’s handling of relations with our most important economic partner and the leading strategic power in Asia.

12 July 2025

Netanyahu leaves Washington without a Gaza ceasefire, just like he wanted

Benjamin Netanyahu is sabotaging talks, hoping Donald Trump will blame Hamas if negotiations fail.

12 July 2025

US, China and Australia – an open letter to the PM

Dear PM Albanese, on Monday 30 June, the Chinese Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, had a letter published in The Australian entitled China and Australia are friends, not foes. This should never have been in question. It’s best to read the full version on China’s Embassy website.

12 July 2025

Imperial hypocrisy about 'terrorism' hits its most absurd point yet

The US has removed Syria’s al-Qaeda franchise from its list of designated terrorist organisations just days after the UK added nonviolent activist group Palestine Action to its own list of banned terrorist groups.

12 July 2025

The greatest irony in our contemporary history

I just read the Sunday Age articles by Chip Le Grand. The writer and The Age have been engaged in a vicious propaganda campaign against the increasing mass protests in Australia that have also involved large numbers of artists, writers, academics and students opposed to the Gazan genocide.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

13 July 2025

Kostakidis to go before court, after judiciary recognises anti-Zionism is not antisemitism

Mary Kostakidis should hold her head up high right now, because of all the Australian journalists who are honestly calling out the holocaust that Israel is perpetrating against the Palestinians.

12 July 2025

Netanyahu leaves Washington without a Gaza ceasefire, just like he wanted

Benjamin Netanyahu is sabotaging talks, hoping Donald Trump will blame Hamas if negotiations fail.

12 July 2025

The greatest irony in our contemporary history

I just read the Sunday Age articles by Chip Le Grand. The writer and The Age have been engaged in a vicious propaganda campaign against the increasing mass protests in Australia that have also involved large numbers of artists, writers, academics and students opposed to the Gazan genocide.

12 July 2025

Gaza: There comes a time when silence is betrayal

Last week I spent a day fasting, joining medical colleagues and other healthcare workers in a rolling hunger strike to protest what is happening in Gaza. Why are we doing this?

11 July 2025

Antisemitism envoy's report 'Trumpian'

The report of the Albanese Government’s antisemitism envoy, Jillian Segal, contains recommendations that will lead to erosion of freedom of expression and the right to protest.

11 July 2025

'It is not antisemitic to criticise Israel,' says Federal Court judge – and the Executive Council of Jewry agrees!

In the light of the revelations in the Lattouf v ABC decision about the way in which the Israel lobby hounded the ABC, the judgment in the recently decided Federal Court case Wertheim & Goot v Haddad is both significant, “interesting” and certainly more than revelatory.

11 July 2025

US sanctions UN expert Albanese over criticism of Israeli genocide

One critic said Secretary of State Marco Rubio's crude effort to sanction Francesca Albanese only serves to establish that the US is an international outlaw.

10 July 2025

The story most Israelis are not allowed to hear

I write this in quite a distressed state. On Sunday, I watched the award-winning documentary film – “No Other Land”.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

12 July 2025

Albanese’s visit to China is a moment for statesmanship

Membership of the Chinese Communist Party has just exceeded 100 million. It has long been the largest political party in world history.

12 July 2025

Albanese’s China mission – managing a complex relationship in a world of shifting alliances

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese leaves for China on Saturday, confident most Australians back the government’s handling of relations with our most important economic partner and the leading strategic power in Asia.

12 July 2025

US, China and Australia – an open letter to the PM

Dear PM Albanese, on Monday 30 June, the Chinese Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, had a letter published in The Australian entitled China and Australia are friends, not foes. This should never have been in question. It’s best to read the full version on China’s Embassy website.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Write the true history of this conflict

Bob Pearce — Adelaide SA

Explaining the inexplicable

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

Leave Donald Trump out of it, Greg Barns

Stephen Saunders — O'Connor

Context and memory missing

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041