19 July 2025

Time for Foreign Minister Wong to put her foot down

In an ideal world, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) should be the government’s principal agency in seeing that relations with other countries best serve Australia’s interests.

19 July 2025

The collapse of civilisation

Days after turning 100, former Malaysian prime minister Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad posted his reflections on the state of the world.

19 July 2025

Trump makes tariffs example of Korea, Japan – Asian Media Report

In Asian media this week: No trade deal exceptions for US allies. Plus: An expert in a government of flunkies; Sex-scandal monks had lives of status and privilege; Corruption stymies Myanmar earthquake recovery; Anwar’s leadership glow starting to fade; 'Comrade' is out-of-fashion in Communist China.

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

19 July 2025

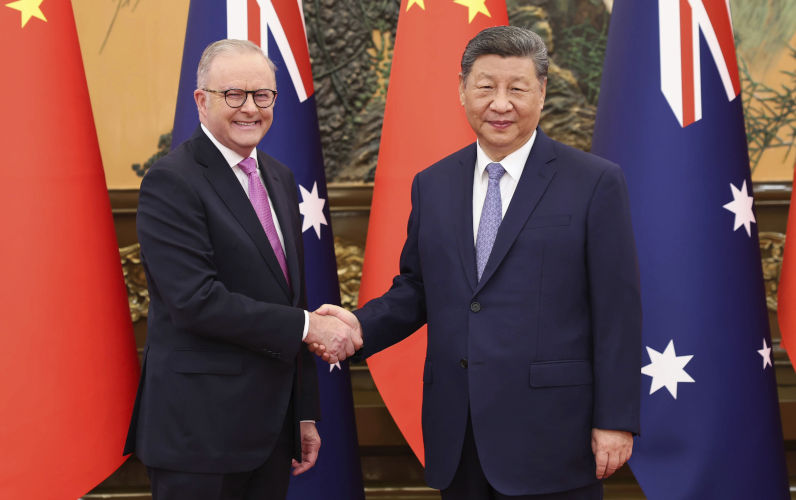

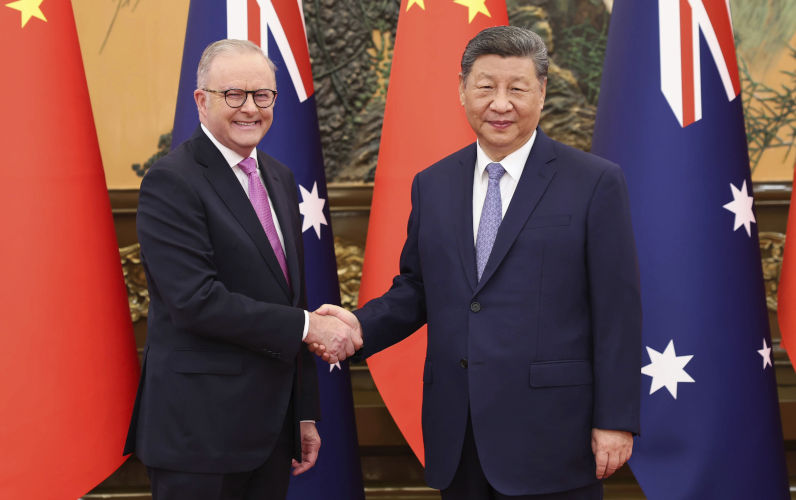

Common interests the basis for stronger China-Australia relations

Neither a port controversy nor any third-party interference cast a shadow over the trade and business focus of Albanese’s trip to China.

19 July 2025

12 years on, are we not yet tired of cruel policies towards asylum-seekers?

In Australia, 2025, Progressive Patriotism is now, apparently, our political modus operandi and, as Anthony Albanese ambitiously explained, it can be “a symbol for the globe in how humanity can move forward”.

19 July 2025

Tasmania’s snap election 2025: How did we get here and where are we going?

Tasmanians are going to the polls on 19 July as the result of a snap election more than two years early.

19 July 2025

Collateral damage? Focus on the principle, not the fallout

Among his many defects, Donald Trump is a vengeful obsessive. Which is why poor Indonesians (that's about 40 million of the 285 million rice-eaters) could soon be paying more for their essential starches.

19 July 2025

Antisemitism, free speech and a dangerous redefinition: How one envoy is rewriting the rules

The recent synagogue fire in Melbourne is being used as a blueprint for sweeping changes to Australian law.

19 July 2025

Slaying the juggernauts

Barbara Preston’s recent reflection on Australia’s school funding system offers a quietly devastating insight into the paradox of public education reform.

19 July 2025

Israel's final Gaza solution

Reports of a shocking Israeli Gaza solution that aims to ethnically cleanse Gaza of all Palestinians by establishing so-called Humanitarian Transit Areas or concentration camps has surfaced in Israeli and other media.

18 July 2025

The Tasmanian election on 19 July won’t fix the mess

A Joint Commonwealth/State Health Commission could help address health failure.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

19 July 2025

Antisemitism, free speech and a dangerous redefinition: How one envoy is rewriting the rules

The recent synagogue fire in Melbourne is being used as a blueprint for sweeping changes to Australian law.

19 July 2025

Israel's final Gaza solution

Reports of a shocking Israeli Gaza solution that aims to ethnically cleanse Gaza of all Palestinians by establishing so-called Humanitarian Transit Areas or concentration camps has surfaced in Israeli and other media.

18 July 2025

Despite denials, Australia has exported F-35 parts to Israel

Leaked documents show Canberra has been supplying Israel with the means to maintain F-35 fighter jets so it can continue its genocidal campaign in Gaza, Peter Cronau and Kellie Tranter report.

17 July 2025

An ambitious plan to combat antisemitism or an effective plan to silence Israel's critics?

I watched the 7.30 interview with the special envoy to combat antisemitism, Jillian Segal, with mounting alarm. By the end of the interview, I was afraid for the future of Australia.

17 July 2025

Israeli settlers kill, destroy and steal with impunity

This week there was another attack on a religious institution. No, not in Australia but in the ancient Christian village of Taibeh, a Palestinian village in the Occupied West Bank.

16 July 2025

The Israel lobby stands loudly condemned for its silence

Reflect for a moment, as you read this piece, what is happening in Gaza.

16 July 2025

Systematic bias: how Western media reproduces the Israeli narrative

If words shape our consciousness, then the media holds the keys to minds.

16 July 2025

Jillian Segal 'won’t dictate' to husband over $50,000 to Advance

The special envoy seeking to dictate the nation’s speech has suggested it was her husband who was responsible for $50,000 given to far-right group Advance — and that she won’t “dictate” his actions.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

19 July 2025

Common interests the basis for stronger China-Australia relations

Neither a port controversy nor any third-party interference cast a shadow over the trade and business focus of Albanese’s trip to China.

18 July 2025

Round up the usual Chinese suspects

It’s a big week for headlines – and an even bigger week for fear. With Prime Minister Albanese landing in China, our media wasted no time rounding up their usual suspects.

18 July 2025

Headline news: Australia and China

The People’s Daily of 16 July featured the meeting between President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in top position on page one.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Tassie's health problem has been building a long time

Ian Ian De Landelles — Murrays Beach

Our democracy – taking the easy road to oblivion

Chris Young — Surrey Hills, Vic

Get capitalism under control first

Bob Pearce — Adelaide SA

FARMS and Usans

Ian Daniels — Brisbane