NATO enlargement enthusiasts look to the Indo-Pacific

July 13, 2023

Lord Ismay, NATOs first secretary-general (SG), famously said the purpose of NATO was to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down.

The end of the Cold War raised hopes of significant changes to the basis of international relations and world order.

Yet the idea and possibility of war were not eliminated from international relations. Human societies are still divided by disputes over beliefs and interests and war cannot be ruled out. National power is inherent in the system of independent states and military force is inherent in national power. Battlefield power has been, is and will remain the arbiter of the destiny of nations: their classification as great powers or minor states, rise and fall, territorial boundaries, even their very emergence and extinction. By determining the nature and identity of great powers, force is the decisive element in the structure of any given international system.

After the Cold War, NATO became an alliance looking for a new role. Its purpose was twisted to keep Americans in, Russians down, and the United Nations out. Now that Russia is a much diminished power an impoverished, geographically and demographically shrunken shell of its superpower glory NATOs purpose might be changing once again to kick the Russians while down, help the Americans out, and box the Chinese in.

Should Australia put on the deputy sheriff star once more to ride with the NATO posse? Instead, Australia might be better advised to look for ways todissuade the US from going to war over Taiwan, and to restrainfrom committing to that war effortin advance should it eventuate.

NATOs Indo-Pacific delusion

NATO created and sustained the environment of military security, political stability and intensive economic cooperation among the great historical enemies of Europe such as Britain, France, Germany and Italy. Its supporters also credit the alliance with having deterred the Soviet Union from attacking a member, although there is no evidence that they ever had any such designs. In the historic transition from the Cold War to a new, undefined, era, the military, bureaucratic, organisational and political assets created by NATO over four decades were a force for stabilisation during a period of turbulence and rapid change, and also a tool for sculpting the emerging new order. But then its leaders were seduced by the temptation to turn what had been a purely defensive alliance inside Europe into one for projecting collective military force outside Europe.

Former Prime Minister (PM) of Norway (200001) Jens Stoltenberg took office in 2013 as the 13th (current) NATO chief. In an interview with Bloomberg in November and then again at the 2023 Munich Security Conference in February, he warned NATO counties not to repeat with China the mistake they made with Russia, of over-dependence on an authoritarian regime. Security considerations must be factored into decisions alongside commercial calculations, he insisted. The Ukraine war demonstrates that security is not regional, it is global. What is happening in Europe today could happen in Asia tomorrow.

His predecessor as NATO SG from 200914 was Denmarks former PM (200109) Anders Fogh Rasmussen. In an Al Jazeera discussion with journalist Mehdi Hasan on 17 April 2015, Rasmussen described NATO as the most successful peace movement the world has ever known. US Admiral James Stavridis (retd), the 16th Supreme Commander NATO, wrote in Time magazine on 15 April 2019 (to mark the alliances 70th anniversary) explaining Why NATO is Essential for World Peace. Their claims echo in my memory from the great peace movements of the 1980s across Europe and in Australia and New Zealand.

This may have been true in the past but is delusional in present circumstances.

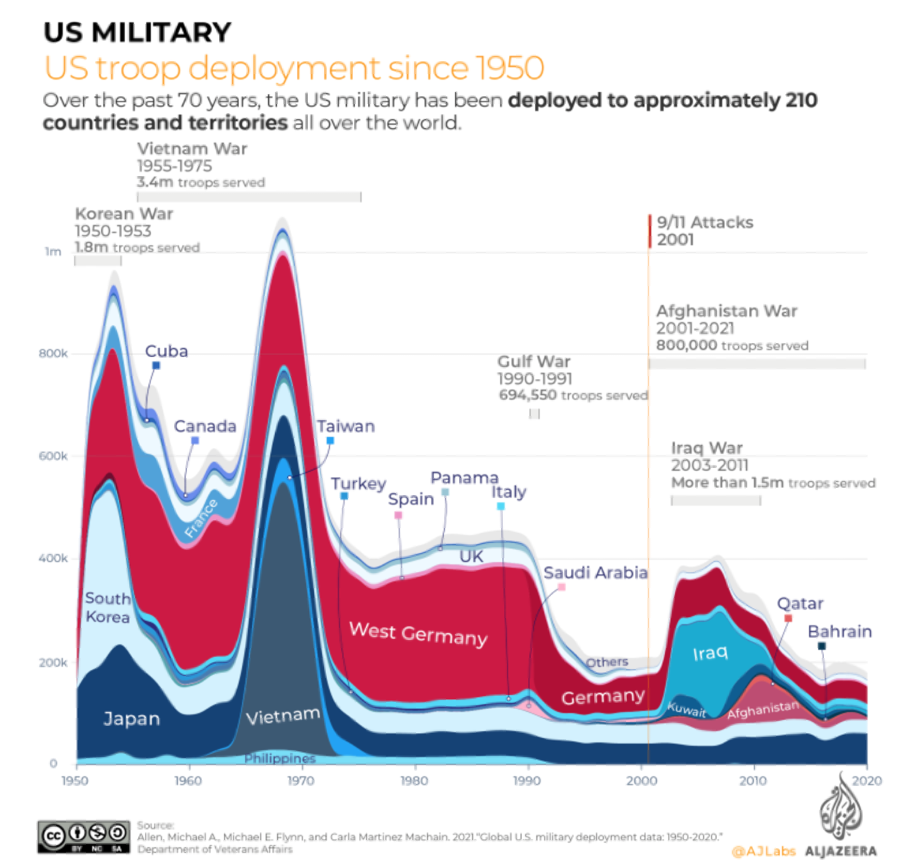

Since 1945, the US has bombed more countries, used force overseas more than any other country, and engaged in regime change of governments insufficiently deferential to US edicts and accommodating of US interests by means of sanctions, subversion and military interventions more frequently than any other country. According to the annual report on this topic from the Congressional Research Service on 7 June, between 1798 and April 2023, the US has deployed force overseas (as distinct from the actual use of force) a total of almost 500 times, with 57 per cent of these occurring after the end of the Cold War.

No other country comes even remotely close to the United States for the number of military bases and troops stationed overseas and the frequency and intensity of its engagement in foreign military conflicts. The US by itself accounts for around four-fifths of all foreign military bases. According to Everett Bledsoe of The Soldiers Project, the US operates some 750 foreign military bases located in around 80 countries, compared to 145 British, around three dozen Russian, and five Chinese. David Vine, co-founder of the Overseas Base Realignment and Closure Coalition, also identifies 750 US foreign military bases.

US-led NATO military intervention in Kosovo in 1999 was an act of aggression that violated international law, the UN Charter and NATOs own charter. The no limits enlargement of NATO, that has taken it relentlessly closer to Russias borders directly, failed to deter and instead provoked a Russian military operation. The two together Kosovo 1999 and NATO enlargement suggest to some critics of Western adventurism, for example Unherd columnist Thomas Fazi, that NATO has caused Europes post-Cold War security architecture to collapse.

What if the neocons, who do seem to be back in charge in Washington and deeply immersed in their preferred playbook of militarised responses to foreign hotspots, are engaged in preparations to repeat this manoeuvre vis–vis China over Taiwan?

NATO is limited by its charter to the North Atlantic

This is where Paul Keatings spray at Stoltenberg becomes relevant. Displaying characteristic sharpness of tongue not mellowed by age, Keating describes Stoltenberg thus: Of all the people on the international stage the supreme fool among them is Stoltenberg, who, by instinct and by policy, is simply an accident on its way to happen. Keating adds that NATOs:

continued existence after the end of the Cold War has already denied peaceful unity to the broader Europe, the promise of which the end of the Cold War held open . Exporting that malicious poison to Asia would be akin to Asia welcoming the plague upon itself.

In Article 5 of the treaty, states parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all necessitating individual or collective response, including the use of force. Article 6 clarifies that an armed attack under Article 5 is deemed to include an armed attack: (i) on the territory of any of the Parties in Europe or North America, and (ii) on the forces, vessels, or aircraft of any of the Parties, when in or over these territories or any other area in Europe (my emphasis in both clauses).

The language of the two articles reflected the US desire to keep the alliance as an arrangement to contain the Soviet Union and avoid turning NATO into an alliance to uphold European colonial empires.

In December 1961, after years of fruitless diplomatic negotiations with Portugal to withdraw from Goa more than four centuries after it was colonised, the Indian military marched in to end the last vestige of European colonial rule in India. Portugal had tried to protect its occupation by amending its constitution in 1951 to declare Goa as an overseas province, and as such an integral part of Portugal, not a colony. This was a transparent stratagem to extend NATOs protection to Goa. Even while criticising Indias resort to force, the other NATO members refused to intervene in the dispute, citing Articles 5 and 6.

The Asia-Pacific Four (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea) seem willing to become accomplices to theglobalisation of NATO to protect US primacy and contain China. They are also entering into the so-called global partners group with individually crafted arrangements with NATO, or supplementary pacts likeAUKUSthat provide a hinge to NATO. Japan has concluded a new partnership agreement with NATO and the latter will be opening anoffice in Tokyo.

However, President Emmanuel Macron of France the one NATO power with actual territorial interests in the Pacific is reported to have blocked the alliances planned extension to Asia, including an office in Tokyo. Insisting that this would shift the remit too far from its original focus, an Elyse Palace official said: NATO means North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, adding that NATO Articles 5 and 6 are geographic.

Currently the US has around 170,000 of its military personnel deployed overseas. Little wonder that Richard Cullen suggests the Department of Defence should be renamed the Department of Attackas a cost-free means to elevating the intimidation level. Theres also the problem of the readiness with which the US weaponises trade, finance, and the role of the dollar as the international currency; and its history of regime change by means fair and foul.Many countries in the rest of the world now perceive the willingness of Western powers to weaponise their dominance of international finance and governance structures as a potential threat to their own sovereignty and security.

At a press conference in Brussels on 3 August 2009, Rassmussen said NATO is a community of democracies defending common values: freedom, peace, security that is doing more, in more places, than it ever has before. Dreams of extending its coverage and footprint to Asia and the Pacific are the latest manifestation of a revanchist neocolonial mindset.

Firstly, Portugal was not democratic when it was founded. Second, not all of Europes longest established democracies are members of NATO. Switzerland has jealously protected its neutrality. Nevertheless, it is true that almost all the other democracies in the North Atlantic are NATO members.

Moreover, not all NATO members have a colonial past. But it is the case that all the historical European colonial powers are members of NATO: in alphabetical order, Belgium, France, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the UK. Many Western countries are currently convulsed by demands to decolonise and cleanse their history, statues, museums and curricula of remnants and reminders of colonial sins. How odd then that they should risk reviving memories of colonialism with a collective move into the Indo-Pacific on the security dimension. Werent the optics bad enough, when AUKUS was first announced in September 2021, of three stale, pale and male Anglo-Saxon leaders asserting the intent to shape the destiny of the Indo-Pacific?

For more on this topic, we recommend: