Peter Fry - NZ style voting for Australia?

May 22, 2022

Many Australians see New Zealands MMP voting system as a complex German-based foreign contraption which has little to offer us. Pete Fry argues that for its users it is a simple responsive transparent process which could help to improve our trust in politics by making our Parliament more representative of the majority of Australians.

“We face an uncertain future which requires imagination, realistic analysis and an open mind. Unfortunately, most Australian politicians lack these qualities as they study the omens from focus groups in marginal electorates.” (Cavan Hogue P&I 11/05/2022)

Cavan Hogue ends his excellent piece on the need for a more independent Australian foreign policy with a reference to the often-ignored reason why Australia’s political system is so incapable of delivering the sort of government most Australians would like.

In the midst of another election it is obvious that the shape and direction of the new incoming government will be largely determined in a handful of marginal electorates. Voters in these electorates are studied and targeted relentlessly by the major parties and election campaigns are explicitly developed around the often quite ignorant beliefs of the minority of voters in that minority of seats who may consider changing their vote.

Its startling to think that perhaps ten percent of voters in only ten percent of seats - a mere one percent of Australian voters - are the ones who decide the outcome of Australian elections. And the major parties, from their research through election after election, know what polling booths are used by these voters and can deduce from that the streets they live in and the shops they go to, the sports grounds they use and the traffic lights they drive through. The 90 percent of us who live in ‘safe’ electorates have long been used to a situation where our views at election time become even more irrelevant than they usually are.

This is what makes it possible, for example, that for many years now about 70% of Australian voters have wanted constructive action on climate change, yet the major political parties have been able to scrape into office on the often-manipulated views of a tiny unrepresentative number of electors in marginal seats and, pressured by vested interests, have persisted in ignoring the majority’s views on climate change.

Our democracy is in reality a misshapen unrepresentative and out of date form of governance, in which a range of idiosyncratic factors in often quite unrepresentative electorates can usually determine what political party will be chosen to govern the whole of the country.

But its not hard to imagine a form of election which would be far more representative. If people could simply vote for what party they want to govern the nation and then the number of votes for that party and its policies were simply represented by the number of seats in the parliament allocated for that party, then we would have a parliament which could genuinely represent the views of people across the country.

We don’t have to look too far for an example of this system working well. In the last century New Zealanders had the courage to update their constitution and today its a very modern, sophisticated but simple to understand voting system.

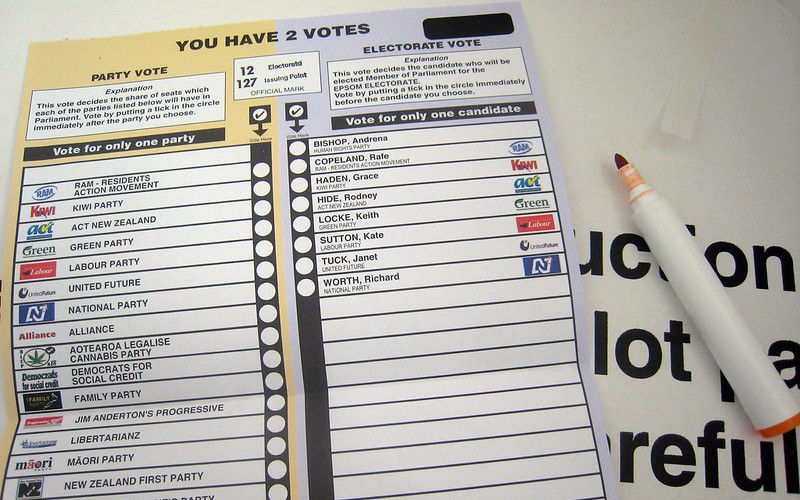

At the core of the New Zealand system is the idea that each voter gets 2 votes. She gets to vote for a local candidate to represent her local electorate. And she also gets to vote for the political party she would like to run the country.

When the votes are counted these questions are decided quite separately.

First of all, the representatives of local electorates are decided and allocated their seats in the house. Most of them will be party representatives as well.

But the number of seats for local representatives only constitutes about two thirds of the total number of seats in the house. The parties also each have a list of extra representatives who are added to the local representatives, topping up each party’s numbers until the total of party numbers in the house fairly accurately represents the proportion of votes across the whole country that each party receives.

So in a very simple way, the majority in each district gets the candidate of their choice, and at the same time, the voters for each party are represented in Parliament in proportion to their support across the country. New Zealanders apparently like it. According to Pew Research, NZ has the least dissatisfaction with government of all developed countries. .

The fact that so-called ‘proportional’ systems frequently require parties to negotiate to form temporary coalition governments has in the past been derided as a form of weakness. But in todays world it is more of a strength, enabling as it does the empowerment of the range of minorities and political views which we find in modern educated and multicultural societies.

One of the side effects of this system also is that the leaderships of major parties in the house are frequently not elected as local district representatives, they are on the party lists. For instance, Jacinda Adern does not represent any particular local electorate in New Zealand. This has the effect that, unlike Tony Abbott, and possibly Josh Frydenberg or Tim Wilson, she cannot be toppled by a campaign attack in a local electorate. She has campaigned nationally to be the leader of the country and her position will only be threatened by a collapse of national support for her or her party.

In the New Zealand electoral system there are additional frameworks specifically for New Zealand conditions, particularly the arrangements for Maori electorates, so that Maori representatives and their views are integrated into the Parliamentary process. There are also particular thresholds for representation and, being a unicameral legislature with no form of senate, there are quite different processes for the review of pending legislation.

But, in essence, the New Zealand voting system makes it easy for voters to understand the process and easy to understand the results. And, unlike the Australian system, every vote has equal value, with the idiosyncrasies and peculiarities of individual electorates having little impact on the outcome of broad voting trends across the nation. If New Zealand’s MMP (Mixed Member Proportional) system were adopted here, Australia’s preferential voting arrangements could be incorporated into the local electorate ballots.

The prospects of introducing such a system in Australia any time soon are of course quite poor. It would mean considerably expanded representation of minor parties in the House of Reps. at the expense of the major parties. The Greens for instance have about 10% of the popular vote nationally, twice that of the Nationals, but under the current system have less than 1% of the seats in the House of Representatives. But it is hard to see a circumstance where either of the major parties in Australia would, any time soon, follow New Zealand in giving up their privileges to move the country towards a more representative electoral system.

At present less than half of Australians would be in favour of a substantial change to our electoral arrangements, however public disgust in politics can be expected to continue to rise and should be alarming to those who wish to preserve the status quo. Pew research last year found that dissatisfaction with politics and government in Australia was twice that of New Zealand. And according to a current Triple J survey only 2% of young Australians believe the present crop of politicians are working in the interests of young people. And only 13% consider our pollies are working in the best interests of the country.

These figures indicate deep levels of alienation amongst the young. If these views develop into an anger at how our electoral system is not delivering the politicians with the imagination and realism the country needs, then real change might not be so far away after all.

Pete Fry is a former ABC Radio documentary maker who is a member of the Greens and whosemy grandparents were New Zealanders.