Political Polarisation in the US - Part 3: Causes

July 28, 2023

One of the great claims for representative democracy and federations is that they provide a uniquely successful way of dynamically negotiating, rather than suppressing, social differences and tensions. So, when it appears to be failing to do that in one of the world’s oldest and most successful democracies it is worth asking “why has this happened”?

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

…

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

W B Yeats The Second Coming

And what rough beast slouches toward Washington be born again? (with apologies to Yeats)

Introduction

In Part 1 we charted the rise of pernicious polarisation in the US and noted that it is an extraordinary contrast with other democracies across the world. In Part 2 we showed how this polarisation has developed a geographic dimension pitting state against state and the Federal Government. One of the great claims for representative democracy and federations is that they provide a uniquely successful way of dynamically negotiating, rather than suppressing, social differences and tensions. So, when it appears to be failing to do that in one of the world’s oldest and most successful democracies it is worth asking “why has this happened”

What has caused polarisation?

Different life experiences - income, ethnicity, education

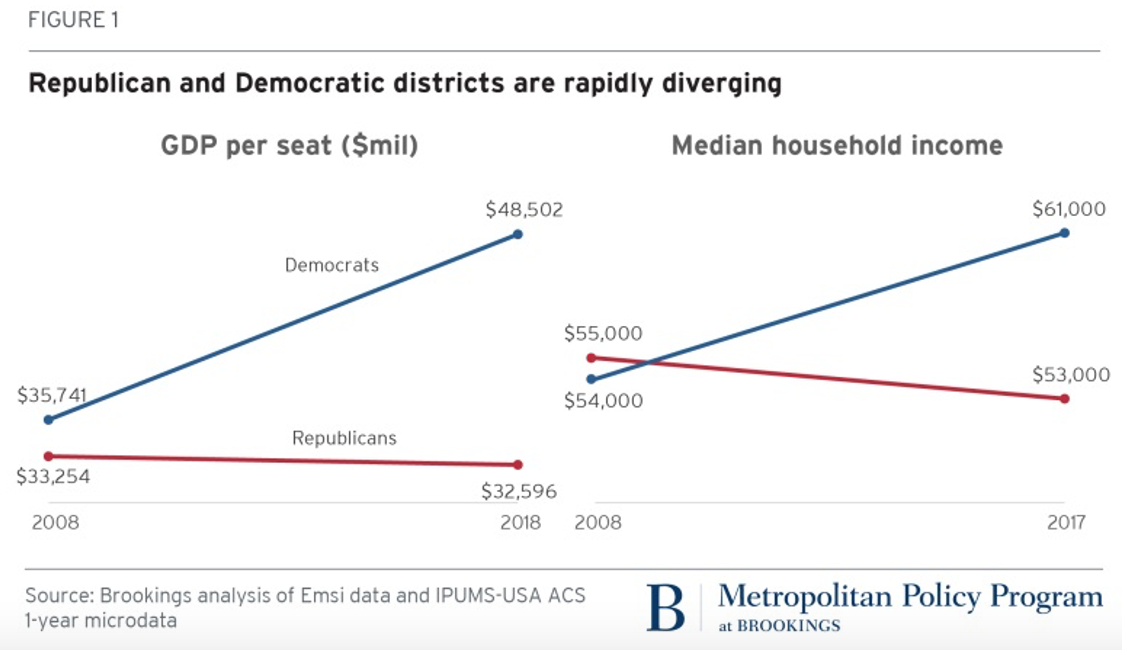

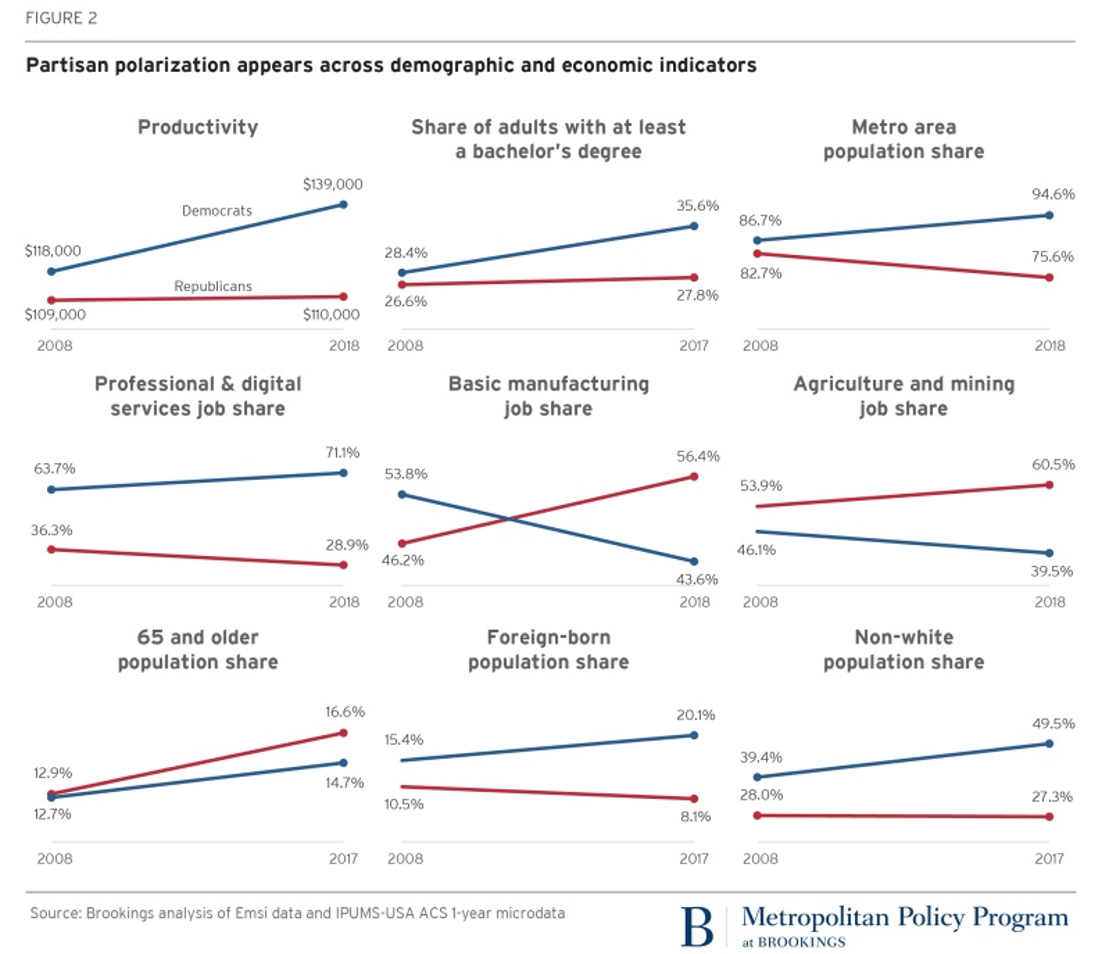

Republican and Democrat districts have shown diverging trends across income, ethnicity and education. There are also differences in the degree of and form of religious affiliation. These divergences have echoed and possibly caused increasing affective polarisation.

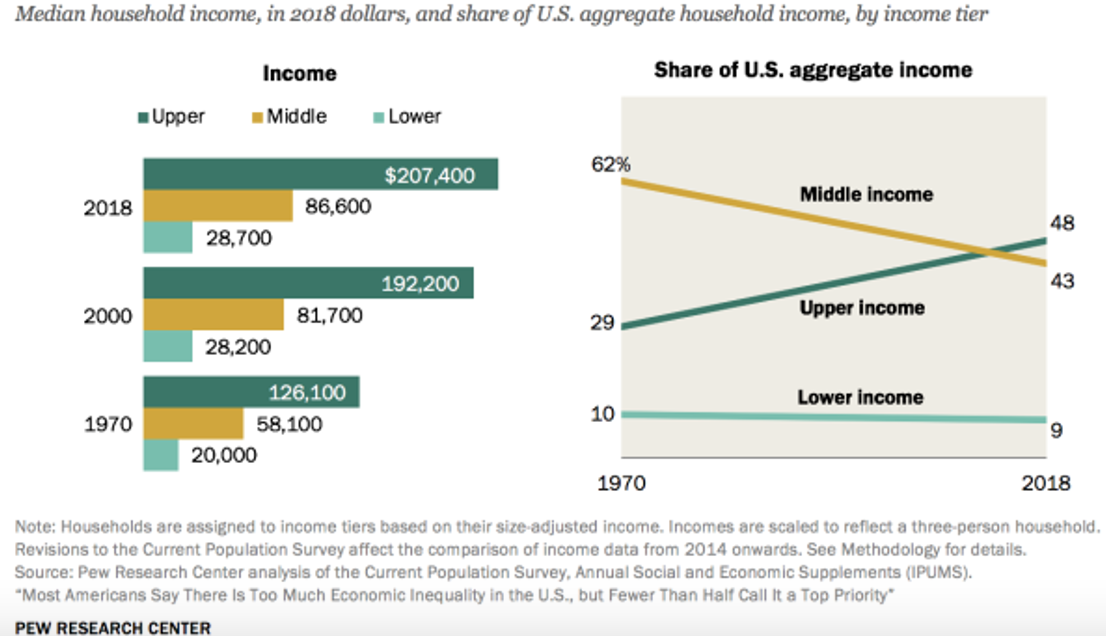

The changes in real median household income between Democrat held districts and Republican ones are particularly striking. The actual decline in real household income in the Republican districts would help explain the attractiveness of the Make America Great Again slogan to many. This is echoed more broadly across US society. Inequality in disposable income has increased by more than 20% since 1970, averaged across a range of measures.

What is particularly striking is the increase in income of the top 5-10% of families. “One widely used measure – the 90/10 ratio – takes the ratio of the income needed to rank among the top 10% of earners in the U.S. (the 90th percentile) to the income at the threshold of the bottom 10% of earners (the 10th percentile). In 1980, the 90/10 ratio in the U.S. stood at 9.1, meaning that households at the top had incomes about nine times the incomes of households at the bottom. The ratio increased in every decade since 1980, reaching 12.6 in 2018, an increase of 39%.” (PEW RESEARCH CENTRE Trends in Income and Wealth Inequality January 9 2020). In Australia the picture is remarkably different. The ratio of individual taxable income at the 10th decile ($29,910) to that at the threshold of the top 10% ($131,500) is 4.39.

The gaps in income between upper - income and middle - and lower - income households are rising, and the share held by middle - income households is falling

The changes in income are echoed in the increasing predominance of “knowledge” work in Democrat districts and manufacturing and agriculture in Republican seats. Free trade, a floating exchange rate, decarbonisation of the economy and the strength of US advanced digital technologies and the financial services sector have seen older and simpler manufacturing decline and agriculture placed under increased pressure. Technological change has hollowed out the middle class.

It is also impossible to ignore the fact that Democrat districts have an increasing proportion of non-white and foreign born voters while the reverse is true for Republican ones. History and race/ethnicity matter in the divergence between Republicans and Democrats. The Pew Center reports

“The gaps (between Democrats and Republicans) are substantially wider on some political values, especially those related to guns and race, than others. For two political values on whether guns should be generally more or less available (not specific gun policies), the average difference is 57 percentage points. An overwhelming share of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (86%) say the nation’s gun laws should be stricter than they are today; just 31% of Republicans and Republican leaners say the same. The partisan differences on political values related to race are nearly as wide (55 points). For example, Democrats are seven times as likely as Republicans to say white people benefit “a great deal” from societal advantages that black people do not have (49% vs. 7%).” (PEW RESEARCH CENTRE DECEMBER 17, 2019 “In a Politically Polarised Era, Sharp Divides in Both Partisan Coalitions”).

Is there an overarching explanation for the rise in polarisation?

Economic inequality v education v identity politics

There is broad agreement that:

- Economic inequality has increased sharply in America since the 1980s with a decline in the real income of many middle and lower income households in this century while the top 1 percent of income and wealth holders have commanded an increasing share of national resources - inequality is at levels unseen since the Gilded Age. The rich are getting richer ever faster.

- White working class voters have progressively deserted the Democratic party over the last 50 years and shifted their allegiance to the Republican party

- Education levels are a strong predictor of party affiliation (although there is considerable overlap) with the Democratic party appealing more to those with higher education levels and the Republican party to those with no, or minimal, tertiary education. And education levels are strongly associated with income level.

- Black and minority workers have continued to have a strong affiliation with the Democratic party, which has also been supportive of a range of progressive issues ranging from immigrants, minority, women’s and LGBTQI+ rights to environmental concerns and particularly climate change.

While class based parties organised around different views on the state’s role in income and wealth redistribution were the norm in most advanced democracies for the first 75 years of the 20th century, this distinction has blurred in the US since the Civil Rights era. White working class voters have increasingly left their traditional home in the Democratic party to support a party, and in the case of Trump, a President, who campaigned on cutting taxes for the wealthy and reducing health support and food stamps for the poor. This seems paradoxical. But a voting person is not necessarily a rational economic person. The Democratic party’s support for progressive social issues, particularly on race, gender and sexuality, is sufficiently distasteful to many white working class voters to overwhelm any appeal its greater emphasis on health and welfare benefits and increasing taxes on the rich and corporations might have.

While the Democratic party continues to have a policy bias toward redistribution it is muted compared with the highpoint of the “great compression” in income and wealth in the New Deal and WWII when top marginal tax rates reached 90%. This social “deal” persisted through the Eisenhower and Kennedy/Johnson years. Progressive social issues have jostled with redistributional justice for priority in the Democratic party of Clinton, Obama and Biden. It appears that the recent deal between Biden and McCarthy has sounded the death knell for Biden’s plan to increase tax on top income earners and corporations.

Republicans, from the Goldwater ascendancy in the party on, have embraced a low tax, small state model - sacrificing social cohesion for a drive to capture the South and, allegedly, lift economic growth.

Americans are faced with a choice between two elite dominated parties. One, the Republicans, financed by wealth wrapped in Flag and Faith and the other, Democrats, dominated by a rich meritocracy vigorously signalling its virtuous inclusiveness. The economic losers are inevitably middle and lower income Americans.

Peter Turchin in End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites and the Path of Political Disintegration and Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-first Century argue that increasing inequality has fuelled identity politics and brought social collapse closer. Piketty has accused the traditional working class parties of abandoning the interests of the poor to focus on the socially progressive ideals of their meritocratic, highly educated leaders. Ironically the Pew Research Center has reported that: “Among Democrats, majorities in all income groups say there is too much economic inequality. But higher-income Democrats are more likely to express concern over this issue: 93% of upper-income Democrats say there’s too much economic inequality in the country today, compared with 84% of middle-income Democrats and 65% of lower-income Democrats”.

The media - in all its forms

The growth of the internet, social media and broadcast media in all its forms has seen a new and worrying set of polarised reverberation chambers developing in American life.

The traditional mainstream media - broadcasting and print - considered it had an obligation to fact check news and used a “cross-fire” approach where contrasting opinions would be debated. Cable news and social media are more likely to identify an audience and present only views that audience finds comfortable and reassuring. Competition often requires these views to be presented in the starkest terms with other views held up to ridicule. The natural human tendency toward confirmation bias in seeking information leads to media consumers editing their own sources of news and opinion to ensure that they are not presented with information that would challenge their beliefs about the world.

The result of this has been plain to see in the internal emails discovered during the Dominion Voting Systems v Fox New Network. It was clear that Fox presenters and owners knew that Trump’s claim of a “stolen election” was untrue - but nevertheless to maintain viewer numbers they implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, supported the allegations of voting improprieties. Social media and on-line opinion sites took a similar approach. The result is that from 50-70 per cent of Republican voters still believe the 2020 election was stolen from them.

While these media changes might not have caused the difference in views held by Democrats and Republicans they have clearly contributed to a deepening of the affective polarisation between Republican and Democratic voters and states. Civil discussion and negotiation of issues across the dividing lines is becoming more difficult.

View all the articles of this four part series.