The Voice referendum dominated the national discourse for much of this year. The result was a major setback for the government.

Fortunately for Anthony Albanese, his loss was quickly swept from the headlines by events in the Middle East. Then came a thirteenth RBA interest rate hike, the High Court’s decision on indefinite immigration detention, and a renewed focus on the cost-of-living crisis.

None of it good news for the government but all of it a distraction from the referendum.

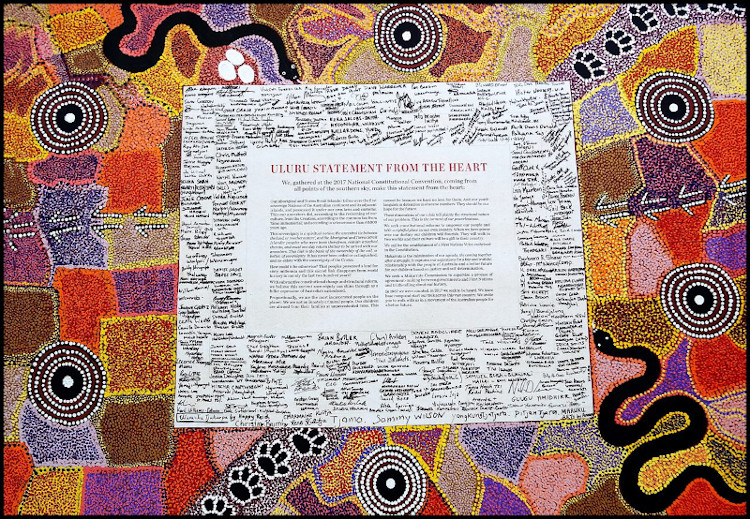

Where does that leave the PM’s policy on Indigenous affairs? When asked about his commitment to the Uluru Statement from the Heart on 15 October, he simply expressed his respect for the outcome of the referendum. There was no mention of treaty or truth telling.

No doubt ALP strategists are currently considering their political options. It would be surprising if they weren’t also analysing New Zealand’s latest election. The rights of NZ’s Māori population featured in the campaign and in the subsequent negotiations that led to the country’s new coalition government comprising the centre-right National Party, the libertarian ACT Party, and the populist NZ First Party .

The previous Labour government took many steps aimed at improving the lives of Indigenous NZers. These included establishing a separate Māori Health Authority, commissioning He Puapua (a report on meeting the goals in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), promoting the use of the Māori language, and pursuing ‘co-governance’ (the sharing of certain governance arrangements between Māori and non-Māori).

However, many of these steps proved controversial and were opposed during the election by National, ACT, and NZ First.

The election was a disaster for the Labour government. Its support crashed to just 27%, down from 50% in 2020. The number of its parliamentary seats nearly halved.

There are many explanations offered for this wipeout – the government’s handling of the Covid pandemic, its failure to deliver on its policy promises, and the cost-of-living crisis. But the explanation that may trouble the ALP in Australia’s post-referendum environment is that significant sections of the kiwi electorate rejected Labour’s progressive agenda on Māori issues.

The best articulation of this explanation comes from Chris Trotter, one of NZ’s leading leftwing political analysts. In ‘Losing the working class’ published by the Democracy Project, Trotter argues that Labour’s ‘co-governance’ initiative triggered the party’s loss of working-class support and was the ‘crucial catalyst’ for electoral defeat.

According to Trotter, the seeds for a break were planted when a Labour government in the 1980s paid lip service to Māori calls for sovereignty and honouring the Treaty of Waitangi without properly understanding their implications. Or explaining them to Labour voters.

Trotter contends that as a result, when the Labour government of Jacinda Ardern moved forward with Indigenous co-governance, ‘the sovereignty grenade finally exploded’. And ‘Labour discovered what it would take to make the working class stop voting for it’.

The coalition agreements between the three parties that comprise NZ’s new government suggest concurrence with Trotter’s hypothesis. They reflect a major reversal of Labour’s progressive approach and speak of ‘ending race-based policies’ and unwinding ‘measures taken in recent years which have eroded the principle of equal citizenship’.

Specific policies include abolishing the Māori Health Authority, stopping He Puapua, requiring government departments to have English names and to primarily communicate in English, ‘refocusing’ (read restricting) the Treaty of Waitangi Tribunal, and confirming that the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples has no legal effect in NZ.

Significantly, the leaders of ACT and NZ First are both Māori.

Given the Voice referendum and the kiwi election, ALP strategists may worry that pursuing too progressive an Indigenous agenda in Australia could alienate many of the party’s traditional working-class voters and come at a significant electoral cost. An unappealing prospect for a government that recorded a primary vote of just 32% at the last election.

However, if the party doesn’t pursue a progressive agenda, it will infuriate its Yes voters, damage relations with First Nations people, and risk losing seats to the Greens and the teals.

If you believe in conviction politics, you’d expect the Prime Minister to maintain his commitment to the Uluru Statement. The question is whether conviction in this case can survive electoral pragmatism.

It hasn’t in the case of Labor’s tax policy in recent years.

Contested ideas like treaty making and truth telling, sovereignty and self-determination, will be part of the national discourse between now and the next election. They’ll be promoted from one side by Indigenous groups and opposed from the other by Peter Dutton and his colleagues.

Fence sitting won’t be an option for the government. Policymaking will be required and there’s no policy path on Indigenous affairs that will satisfy both the cultural progressives and the cultural conservatives in Labor’s base.

There will be conflict, and the challenge for the PM will be to manage the electoral consequences.

In the meantime, he’ll be watching New Zealand closely.