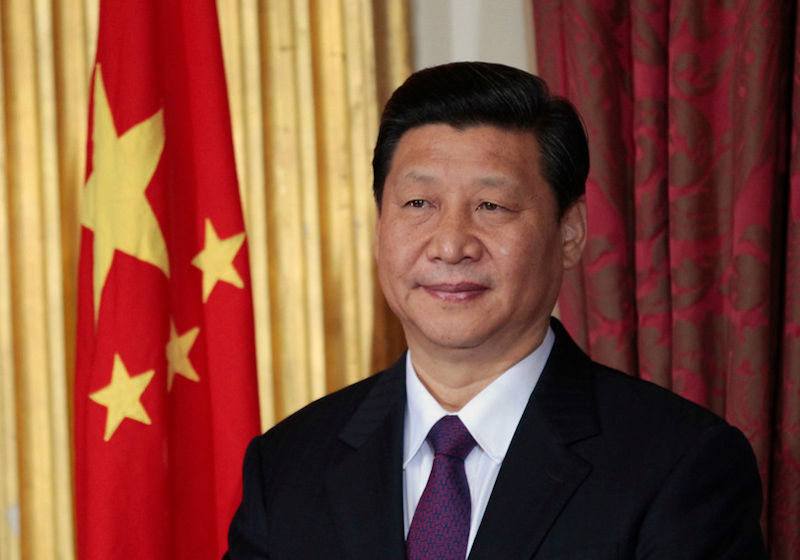

With Chinese President Xi Jinping securing an unprecedented third term in power, fears are mounting that Sino-U.S. tensions may escalate further over Taiwan and economic security, forcing Japan to review its policies regarding Beijing.

Calls are growing in Japan for the government of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to reinforce the country’s alliance with the United States in a bid to ensure peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region by countering China’s increasing influence.

But not everyone believes Japan should remain coupled with Washington in the future.

The regional security environment became more complex in the eight years from around 2012, when Japan was being led by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. He pursued a hawkish foreign policy platform that irritated China, some political experts believe.

Kishida, a self-proclaimed dove, should pursue a well-balanced diplomatic strategy toward Beijing as a fellow Asian nation, distancing Japan from the United States and its attempts to isolate China economically through an array of high-tech restrictions, they said.

Conservative politicians in Japan, like Abe, have traditionally prioritised strong security cooperation with the United States as the best way to challenge the military and economic ambition of the Communist Party-run China.

Abe, Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, who resigned in 2020, said late last year that any emergency surrounding the self-ruled democratic island of Taiwan would also be an emergency for the Japan-U.S. security alliance. Abe’s comments triggered a harsh backlash from China.

Beijing and Taipei have been governed separately since they split in 1949 as a result of a civil war. Xi has repeatedly described Taiwan as a “core interest,” pledging to unify Taiwan and China — by force, if necessary.

To avoid needless conflict in the region, Kishida has to take Xi’s re-election to a new five-year term as a window of opportunity to move past Abe-style diplomacy, which often caused China to adopt a tougher stance toward Japan and frayed bilateral relations, pundits say.

Yoshihide Soeya, a professor emeritus of political science at Keio University, said Japan should “pave the way to coexisting with China” instead of focusing only on strengthening its deterrence against Beijing’s military threat.

Over the past few years, China’s ties with the United States have deteriorated sharply over Taiwan, while China and Japan have been at odds over the Tokyo-controlled, Beijing-claimed Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

In his opening speech on Oct. 16 at the Communist Party’s recently concluded twice-a-decade congress, Xi said China will “never promise to renounce the use of force, and we reserve the option of taking all measures necessary” to unite Taiwan with the mainland.

As a rift between Beijing and Washington has been deepening in the wake of U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in early August, Xi also warned against any interference by the United States or other nations.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken voiced wariness over Xi’s remarks, saying China had made a “fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable, and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline.”

Following the visit by Pelosi, the third-highest-ranking U.S. official, Beijing conducted large-scale military drills in areas encircling Taiwan in retaliation, firing ballistic missiles, some of which fell into Japan’s claimed exclusive economic zone east of the island.

Immediately after the missile launch, then-Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi said, “This is a grave issue that concerns our country’s national security and the safety of the people,” calling China’s action “extremely coercive.”

Jeff Kingston, director of Asian Studies at Temple University Japan, said the episode allowed Japan to subtly make clear its dissatisfaction with the Pelosi visit, with the Kishida administration signalling it “has backed away from Abe’s more bellicose posturing.”

“Japan is eager to reduce tensions,” the scholar said.

Seeds of a different diplomatic approach to China had actually been sown early in Kishida’s tenure as prime minister. A month after he took office in October 2021, he installed Yoshimasa Hayashi, a veteran lawmaker seen as “pro-China,” as foreign minister.

While claiming that Tokyo will “assert what needs to be asserted” to Beijing, Kishida has apparently extended an olive branch.

Also, with this year marking the 50th anniversary of the normalisation of Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations, the Kishida government had some incentive to cooperate with Chinese leaders to prevent bilateral ties from deteriorating.

“There are good chances” of “improving bilateral communication on a range of issues such as supply chain resilience, nontraditional threats to security and climate change,” Kingston said.

But Japanese merchants trading with China are skeptical as to whether the two nations will suddenly become friendly. They say that once Xi tightens his grip on power, Tokyo is certain to be drawn deeper into the growing economic rivalry between Washington and Beijing.

With the world’s second-biggest economy languishing against a backdrop of the country’s all-encompassing “COVID zero” policy, which has stifled domestic spending, Xi is believed to be putting more energy into foreign trade to stimulate sluggish demand at home.

In areas where businesses promoted by Beijing compete with those from the West, for example in digital currency and semiconductor production, the United States will strive to eliminate China from the markets, further intensifying competition between the two major powers, the merchants said.

Takahide Kiuchi, an executive economist at the Nomura Research Institute, echoed the view, saying that in his third term, Xi is expected to “carry out an expansionary economic policy with an eye on overseas markets” to shore up China’s stagnant economy.

Kiuchi added it would be inevitable that China and democratic nations, including the United States and Japan, will be at loggerheads over economic and national security, if Xi pushes for deals with emerging countries in a manner the West views as heavy-handed.

The situation is not helped by Kishida having installed Sanae Takaichi, a parliamentarian known for sharing Abe’s hawkish stance, as economic security minister in an early August Cabinet reshuffle. The move frustrated China, which has labeled her a “right-wing” nationalist.

Nonetheless, a marketing official at Sony, speaking on condition of anonymity, expressed hope the Kishida administration will improve its interactions with the Chinese government, whoever the minister is, so the Japanese electronics giant can concentrate on its business in China.

“China is still a very attractive market for us. We want the Japanese government to understand that we do not want to be exposed to country risk in China,” the official said.

Tomoyuki Tachikawa is Kyodo News English reporter, covering China’s ties with Japan, U.S., ASEAN, Koreas. Often went to Pyongyang. Former Dow Jones/WSJ reporter. MA at GWU.

First published in thejapantimes Oct 27 2022.