8 July 2025

The one-word problem for Israel

The massive, almost universal, support nations have provided Israel since the Hamas attacks is eroding around the world and new research indicates that most people surveyed over 24 countries now have negative views of Israel and Netanyahu.

8 July 2025

When the helping hand holds a machine gun

There’s no precise number of how many Palestinians have been starved to death by Israel’s embargo on food entering Gaza.

8 July 2025

Engulfed in a moral panic about childcare assaults

The moral panic enveloping Australia and the ABC over the existence of child molesters in the childcare system will do this nation no good.

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

8 July 2025

China and renewable energy: The global impact

China’s renewable energy program is not a local curiosity. It marks a turning point in history with profound consequences for the rest of the globe.

8 July 2025

Should Australia legalise commercial surrogacy?

Labour of Love; Magic Happens; The Greatest Gift. These are just some recent Australian news headlines promising good news stories about surrogacy and happy families.

8 July 2025

The Rainbow Warrior 1985-2025 – Nuclear refugees in the Pacific: the evacuation of Rongelap - Part 2

On the last voyage of the Rainbow Warrior prior to its sinking by French agents in Auckland harbour on 10 July 1985 the ship had evacuated the entire population (320) of Rongelap in the Marshall Islands.

8 July 2025

Squad a strategic boon for India and the Quad

Manila is considering expanding the Squad — a security coalition focused on operational maritime deterrence comprised of the US, Japan, Australia and the Philippines — to include India and South Korea.

8 July 2025

Boomers bashing again: Change the rules

A departing editor-at-large from The Australian Financial Review, off to head the IPA, warns of an “intergenerational tragedy” facing young Australians.

8 July 2025

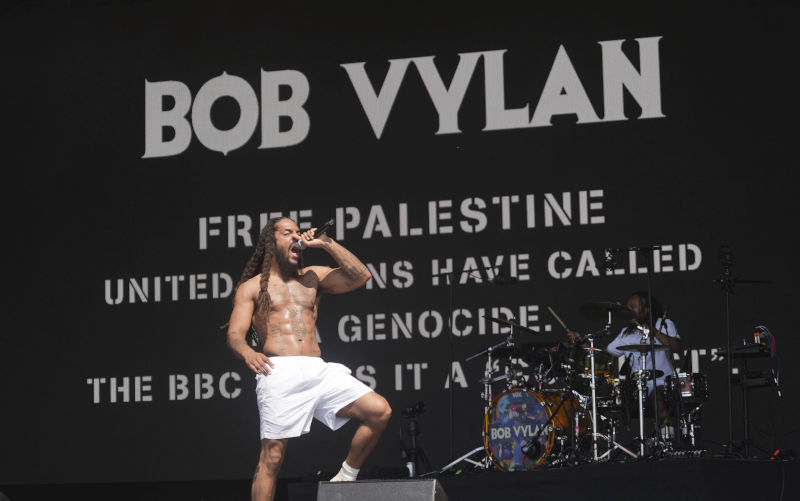

The Empire has accidentally caused the rebirth of real counterculture in the West

Everyone’s still talking about Bob Vylan, and rightly so. A crowd full of Westerners happily being led through a chant of “Death, death to the IDF” at the 2025 Glastonbury Festival was a historical landmark moment for the 21st century, and the group’s persecution at the hands of Western governments is once again highlighting the way our society’s purported values of free thought and free expression go right out of the window wherever Israel is concerned.

8 July 2025

Political unrest, French negotiations and decolonisation in New Caledonia

New Caledonia stands at a precipice. Political representatives from this French Territory are meeting in Paris to try to eke out an agreement over its political future in the dark shadow of the violence of 2024 that saw New Caledonia burn and 14 people — 12 Kanaks and two French military — killed.

7 July 2025

National Anti-Corruption Commission is two years old – Has it restored integrity to federal government?

The National Anti-Corruption Commission opened its doors two years ago this week amid much fanfare and high expectations.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

8 July 2025

The one-word problem for Israel

The massive, almost universal, support nations have provided Israel since the Hamas attacks is eroding around the world and new research indicates that most people surveyed over 24 countries now have negative views of Israel and Netanyahu.

8 July 2025

When the helping hand holds a machine gun

There’s no precise number of how many Palestinians have been starved to death by Israel’s embargo on food entering Gaza.

7 July 2025

J’accuse (Part 2) – The Israel lobby

Readers may recall a piece published here on Pearls and Irritations (J’accuse!... the Jew who accuses his fellow Jews of being antisemites on 23 February, 2025 — in which I wrote about an offensive tweet Mark Leibler (lawyer and leader of AIJAC) posted on X — in which, amongst other things, he described those Jews criticising Israel as “vicious antisemites”.

6 July 2025

Gunning for the Greens over Gaza - Part 1

After the federal election on 3 May, dissection of the Liberals’ turmoil received top billing.

4 July 2025

Genocide in Gaza: History repeats itself

For the past 21 months, I have endured the painful experience of displacement, moving between tents under relentless bombardment in Gaza.

4 July 2025

Food aid or firing squads?

In Gaza today, hunger has a price – and for far too many civilians, that price has been death.

3 July 2025

UN report lists companies complicit in Israel’s ‘genocide’. Who are they?

The United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) has released a new report mapping the corporations aiding Israel in the displacement of Palestinians and its genocidal war on Gaza, in breach of international law.

3 July 2025

Israel’s genocide and German Staatsräson: Thwarting a youth’s political sensibilities

It was the third month of Israel’s genocidal onslaught in Gaza, just before the Christmas break in 2023, when my daughter Lelia came home one day and mentioned an unhappy confrontation with one of the directors of her school, the Freie Waldorfschule Berlin Mitte.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

8 July 2025

China and renewable energy: The global impact

China’s renewable energy program is not a local curiosity. It marks a turning point in history with profound consequences for the rest of the globe.

4 July 2025

China’s rapid adoption of AI demands greater scrutiny of the social impact

In contrast to the perception that Beijing has placed a lot of guardrails on AI, China’s AI regulation so far has been limited.

30 June 2025

China is taking Silicon Valley’s market ‘hacks’ to a whole new level

From blitzscaling to leveraging network effects, China is using the same methods to dominate supply chain and disrupt markets.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Capitalism should be the target

Ted Trainer — Sydney, NSW

Facts sadly don't trump fantasy in the US

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

Israeli McCarthyism

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

Time for rebinding the Good Book

Alyssa Aleksanian — Hazelbrook