This month, support Pearls and Irritations with your tax deductible donation

We continue to see powerful interests shape the headlines and spread misinformation faster than facts in current times. This year, Pearls and Irritations has again proven that independent media has never been more essential. We have continued to push the issues ignored by mainstream media, building our voice as a trusted source for local and global issues. We ask you to support our plans for 2026.

For the next month you can make a tax deductible donation through the Australian Cultural Fund via the link below.

Donate

5 December 2025

Fear versus facts: why migrants strengthen Australia

Australia’s multicultural society is not a modern experiment or a social crisis. It is the product of shared effort, grounded in First Nations custodianship and strengthened by generations of migrants who have helped build the nation’s economy, culture and community life.

5 December 2025

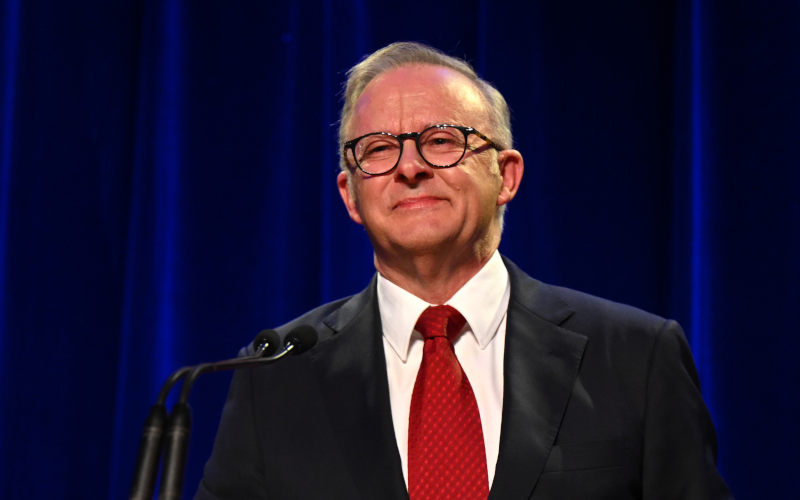

Words or action? Dreyfus and human rights at home

Mark Dreyfus has been appointed Australia’s special envoy on human rights. Is the government prepared to match international advocacy with concrete action at home – by finally legislating a Human Rights Act?

5 December 2025

When foreign policy becomes domestic theatre

Australia’s response to Japan’s rhetoric has been framed as a test of loyalty, but the outrage is largely media-driven. Caution in foreign policy is not betrayal – it is a rational defence of national interest.

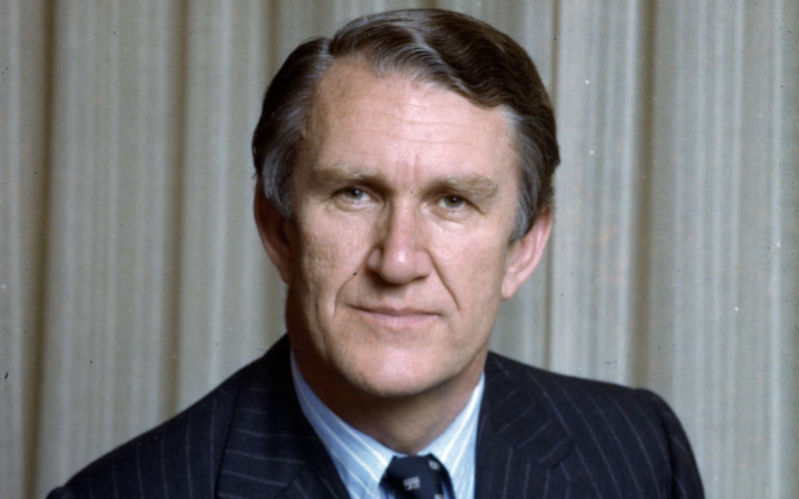

Launching Pearlcasts

The 50th Anniversary of the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government

We kick off with a topic close to our hearts, the 50th anniversary of the Dismissal of the Whitlam Government. We have three of the best sources in the nation taking part: our editor-in-chief John Menadue – the living link to the scandal and the nation’s top public servant at the time; Jenny Hocking, author of The Palace Letters and Australia’s pre-eminent Dismissal historian; and Brian Toohey, the journalist who has dug deepest into the darkest elements of the events.

Go to Pearlcasts

5 December 2025

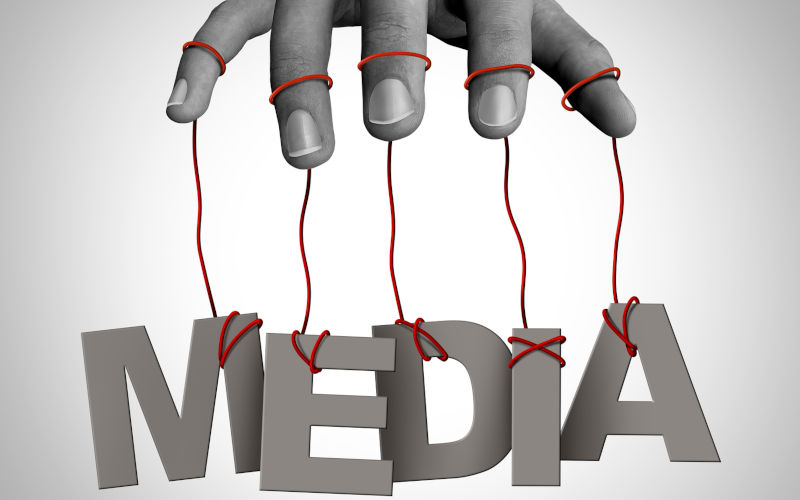

How media coverage helps normalise the far right

Media coverage does more than report on the far right. Through language choices, sensationalism and false balance, journalism can help shift racist politics into the mainstream.

5 December 2025

Trump’s drug war on Venezuela reeks of hypocrisy

Donald Trump’s campaign against Venezuela is less about drugs than power, exposing deep hypocrisy in US policy and raising uncomfortable questions for Australia about its alliance.

5 December 2025

Is the focus on NAPLAN’s ‘top’ schools a good idea?

This year’s NAPLAN results reveal encouraging stories of student progress, but headlines about 'top' schools risk oversimplifying how improvement really happens – and what parents should take from the data.

5 December 2025

A Boyer Lecture that misunderstands Australia’s defence history

The latest Boyer Lecture portrays Australia as trapped by anxiety about the United States. In fact, for decades the country pursued a deliberate, bipartisan strategy of defence self-reliance – abandoned only in recent years.

5 December 2025

Celebrating war crimes is a moral failure, not cultural pride

From ancient Rome to modern Melbourne, societies have repeatedly transformed civilian suffering into spectacle. Celebrating violence against the innocent is not a cultural quirk – it is a profound moral collapse.

5 December 2025

Corruption prosecutions are choking Indonesia’s reform ambition

High-profile prosecutions of Indonesia’s technocrats are reshaping incentives across government and business. When good-faith decisions are treated as crimes, reform, investment and innovation all suffer.

5 December 2025

Book Review: Selling Israel: propaganda, history and contested narratives

Harriet Malinowitz’s Selling Israel examines how Zionist ideology has been promoted through propaganda, history and selective memory, and why separating Judaism from Zionism matters in confronting antisemitism.

4 December 2025

Australia’s immigration 'debate' is rhetoric, not policy

Australia is awash with immigration rhetoric, but little of it is grounded in evidence, clear definitions or serious policy alternatives. Rather than an informed public debate, Australians are being offered slogans, blame and ambiguity.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

5 December 2025

Book Review: Selling Israel: propaganda, history and contested narratives

Harriet Malinowitz’s Selling Israel examines how Zionist ideology has been promoted through propaganda, history and selective memory, and why separating Judaism from Zionism matters in confronting antisemitism.

3 December 2025

Global campaign amplifies call for the release of jailed Palestinian leader Barghouti

An international campaign is calling for the release of Palestinian political figure Marwan Barghouti, arguing his freedom could reshape Palestinian politics and revive peace efforts.

3 December 2025

What charges does Benjamin Netanyahu face, and what’s at stake if he is granted a pardon?

Benjamin Netanyahu has requested a pardon while still on trial for corruption. The move raises serious questions about legal accountability, judicial independence and political survival.

1 December 2025

‘Genocide is not over,’ Amnesty leader says as Israel keeps bombing Gaza

“So far, there is no indication that Israel is taking serious measures to reverse the deadly impact of its crimes and no evidence that its intent has changed.”

29 November 2025

Gaza’s true death toll could be 126,000 or even higher

New research suggests Gaza’s death toll may be far higher than widely reported, with devastating implications for life expectancy, poverty and accountability.

25 November 2025

The ceasefire that isn’t: 400 violations in 40 days

Israel has violated the ceasefire in Gaza hundreds of times since October, using vague or unverified justifications to carry out strike in a recurring pattern of escalation and impunity.

23 November 2025

The UN embraces colonialism: the Security Council and the US Gaza plan

The Security Council's backing of the Trump plan for Gaza ignores international law, punishes the Palestinians, and rewards those responsible for genocide.

21 November 2025

UN Members complicit in genocide

UN Special Rapporteur on Palestine Francesca Albanese discusses why, in her most recent report, she called out more than 60 nations for their collective-crime roles in the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

5 December 2025

When foreign policy becomes domestic theatre

Australia’s response to Japan’s rhetoric has been framed as a test of loyalty, but the outrage is largely media-driven. Caution in foreign policy is not betrayal – it is a rational defence of national interest.

1 December 2025

How soybeans became a fault line in China’s food security

China now buys 60 per cent of the world’s soybeans. That dependency shapes its food security strategy – and its trade battles with the United States.

30 November 2025

New architecture, old assumptions: Australia and the China question

Foreign Minister Penny Wong speaks of balance, equality and a new regional order – yet Australia’s China policy still carries Cold War assumptions that risk strategy, prosperity and peace.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Sir Humphrey and international law

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

A simple solution

Les Macdonald — Balmain NSW 2041

Can he stay or will he go

Hal Duell — Alice Springs

Government funding of private schools should be phased out

Elizabeth Sprigg — Glen Iris, Victoria