3 July 2025

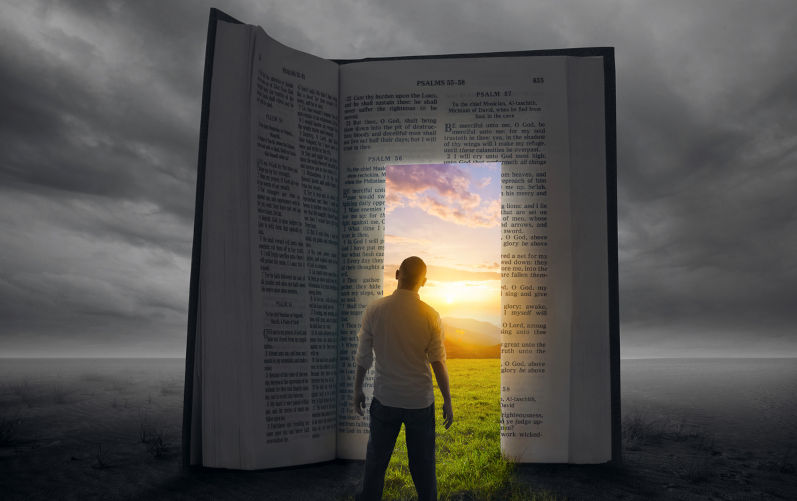

The time has arrived for a comprehensive Middle East peace

The attack by Israel and the US on Iran had two significant effects.

3 July 2025

So... calling for peace isn’t enough, but dropping bombs gets a free pass?

When China submitted a draft UN Security Council resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire between Israel and Iran, the response wasn't debate or discussion. It was suspicion.

3 July 2025

From globalisation to AI: Why history is about to repeat itself

When globalisation loomed on the horizon in the late 20th century, governments around the world faced a choice: open the economy fully or manage the transition strategically.

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

3 July 2025

UN report lists companies complicit in Israel’s ‘genocide’. Who are they?

The United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) has released a new report mapping the corporations aiding Israel in the displacement of Palestinians and its genocidal war on Gaza, in breach of international law.

3 July 2025

The devil's dance with Iran

Iran has been on a hit list of seven countries in a geostrategic plan for the reconfiguration of the Middle East first drawn up by the US in 2001 following the 9/11 attacks.

3 July 2025

Trump’s worldview is causing a global shift of alliances – what does this mean for nations in the middle?

Since US President Donald Trump took office this year, one theme has come up time and again: his rule is a threat to the US-led international order.

3 July 2025

India’s state and central governments still aren’t speaking the same language

The first rule of discussing language policy in India is to leave any expectations of a calm conversation at the door.

3 July 2025

I'd rather a bloodied shark than AI

Until recently, I regarded AI as just another technical assist, a natural enhancement of Google where one finds the perfect word to complete a sentence, or to expand on the broad brush of Wikipedia info.

3 July 2025

Israel’s genocide and German Staatsräson: Thwarting a youth’s political sensibilities

It was the third month of Israel’s genocidal onslaught in Gaza, just before the Christmas break in 2023, when my daughter Lelia came home one day and mentioned an unhappy confrontation with one of the directors of her school, the Freie Waldorfschule Berlin Mitte.

3 July 2025

Australia, the UN and the future of humanity

The Albanese Government is now very well placed to encourage and assist the United Nations, to prevent human extinction, and make our planet habitable for future generations. It has also, now become very urgent that we take comprehensive action on the issues discussed below.

2 July 2025

How spending more on defence harms the nation

Anthony Albanese is taking a battering from ill-informed commentators for thinking Australia can be defended by spending a little over 2% of GDP on its military forces.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

3 July 2025

UN report lists companies complicit in Israel’s ‘genocide’. Who are they?

The United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) has released a new report mapping the corporations aiding Israel in the displacement of Palestinians and its genocidal war on Gaza, in breach of international law.

3 July 2025

Israel’s genocide and German Staatsräson: Thwarting a youth’s political sensibilities

It was the third month of Israel’s genocidal onslaught in Gaza, just before the Christmas break in 2023, when my daughter Lelia came home one day and mentioned an unhappy confrontation with one of the directors of her school, the Freie Waldorfschule Berlin Mitte.

2 July 2025

Gaza’s Hunger Games

Israel is weaponising starvation. The objective is to dismantle all remnants of civil society and reduce Palestinians to herds of desperate scavengers who can be driven from historic Palestine.

2 July 2025

Flour instead of homeland: manufacturing the crisis and the end of the Palestinian dream

Since 4:00 p.m. on 14 May 1948, the Palestinian cause has been one of a homeland seized by force, a land torn from its people by Zionism through weapons and terror.

2 July 2025

Courage needs to be shown in politics – Israel is no longer above the law

In the past weeks, an estimated 500 more Gazans have been killed, bombed out of existence by the IDF or killed while queuing for food.

30 June 2025

Lattouf’s victory, our fight: Standing firm against intimidation

In April 2025, I posted a comment in The Age, sharing how, after 40 years in my Goldstein neighbourhood, I’d never felt unsafe until I was wrongly accused of antisemitism.

29 June 2025

Starvation and profiteering in Gaza (with Francesca Albanese) | The Chris Hedges Report

Francesca Albanese joins Chris Hedges to break down the current starvation campaign in Gaza, and her upcoming report detailing the profiteering corporations capitalising on the erasure of Palestinians.

29 June 2025

Three blows against Zionism in a single day

A court ruling in Australia, an election result in New York and a military setback for Israel, all coming last week, signalled a serious turn of events for Zionism and its supporters, writes Joe Lauria.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

30 June 2025

China is taking Silicon Valley’s market ‘hacks’ to a whole new level

From blitzscaling to leveraging network effects, China is using the same methods to dominate supply chain and disrupt markets.

28 June 2025

No time to dye: ABC’s China bias is licensed to kill credibility

The ABC has long held a reputation as Australia’s sober, publicly-funded bulwark against tabloid sensationalism – the broadcaster you turn to when you want analysis, not alarmism.

28 June 2025

China’s partnership with Muslim world is redrawing global landscape

Once seen as unlikely partners, this axis is now grounded in respect, sovereignty and a shared aspiration for a post-Western world order.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Warfare post-globalisation

Dave Young — NQ

Our catastrophic superannuation system

Richard Barnes — Melbourne

How about a complete 21st century edit?

John Mosig — Kew, Victoria

'Your winnings, sir'

Peter Sainsbury — Darling Point