Pearlcasts

As we review 2025, the temptation is to look for neat summaries and settled conclusions.

Go to Pearlcasts

2 February 2026

Australia’s Trump reprieve masks a deeper strategic dilemma

Australia may have escaped the worst of Donald Trump’s return to power so far. But beneath the surface, Washington’s shift towards spheres of influence is exposing serious weaknesses in Australia’s strategic posture.

2 February 2026

Mass layoffs continue to punish working class under Trump

Major US companies including Amazon, UPS and Dow are announcing large job cuts as employment growth slows, raising questions about the strength of the US labour market under Donald Trump.

2 February 2026

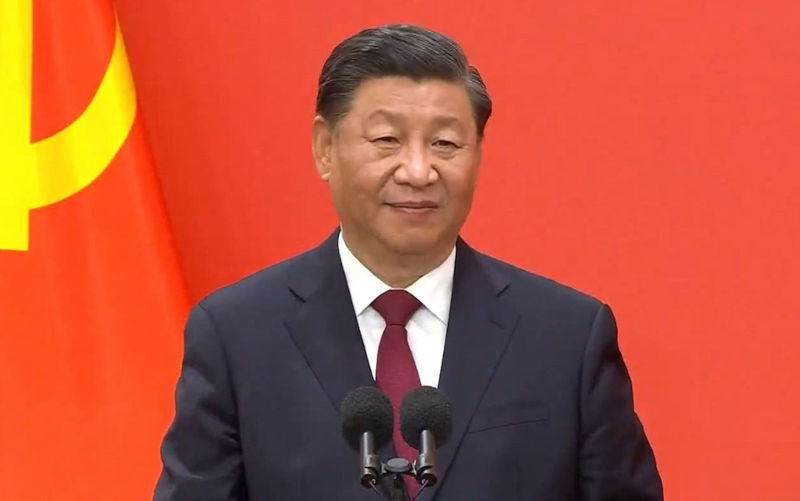

Steadfast state support is key to China winning tech race with US

China’s sustained investment in science, engineering and technology is pulling it ahead globally, while the United States cuts research funding and hollow-outs its scientific workforce.

2 February 2026

Why ‘salvage logging’ undermines a promise to end native forest logging

Despite announcing an end to native forest logging, destructive logging practices continue in Victoria under the guise of firebreaks and post-storm debris removal – with serious consequences for biodiversity, fire risk and public trust.

2 February 2026

What the ‘mother of all deals’ between India and the EU means for global trade

The European Union and India have finalised a sweeping free trade agreement after two decades of negotiations. The deal is as much a strategic signal as a commercial one.

2 February 2026

Australia’s vast sea territories – and the risks we ignore

As great powers revive territorial ambition, Australia is neglecting the strategic and economic value of its remote islands and the vast ocean zones they command.

2 February 2026

When public opinion breaks: ICE, Trump and a political tipping point

Political opinion usually shifts slowly, but history shows that certain events can force sudden, irreversible change. The killings linked to ICE enforcement may mark such a moment in the United States.

1 February 2026

Mark Carney – Values: an economist's guide to everything that matters

Mark Carney argues that treating price as a proxy for value has driven crises in finance, health and climate. His book offers a roadmap for rebuilding trust, fairness and resilience.

1 February 2026

Vaccination, misinformation and the damage done by US policy shifts

The United States’ retreat from evidence-based vaccination policy is accelerating vaccine hesitancy at home and abroad. As misinformation gains official backing, the consequences for public health are already becoming visible – and Australia is not immune.

1 February 2026

Environment: Agricultural emissions are roasting the planet

Together, 45 global livestock companies produce more greenhouse gases than all but eight countries. Plus, crimes against nature are big business that rely on criminal networks, corrupt officials and eager customers, and global warming marches on.

1 February 2026

Does killing dingoes make K’gari safer for people?

The Queensland government’s decision to cull dingoes on K’gari after a tragic fatal incident has sparked debate about public safety, conservation and whether killing wildlife reduces risk to visitors.

Read our series

Latest on Palestine and Israel

29 January 2026

A war without headlines

The annihilation of Gaza has rendered the violence in the West Bank seemingly secondary in the global imagination.

26 January 2026

From international law to loyalty and deals: Trump’s Board of Peace play

The Trump-led Board of Peace points to a shift away from international law and multilateral institutions toward a system built on loyalty, coercion and financial leverage.

24 January 2026

Cultural “cohesion” becomes censorship, and a festival falls apart

Adelaide Writer’s Week was derailed after the withdrawal of an invited speaker, triggering mass author withdrawals and a board resignation. The episode raises hard questions about free speech, institutional courage, and the politics of Israel and Gaza in Australia’s cultural life.

23 January 2026

Bad laws are the worst sort of tyranny – and this one ticks every box

A sweeping new bill to combat antisemitism, hate and extremism was rushed through federal parliament this week with minimal scrutiny and major rule-of-law flaws. Its vague definitions, retrospective reach and expanded executive powers risk undermining rights, due process and democratic accountability.

20 January 2026

The rules are breaking – and the world is watching

The abduction of Venezuela’s president signals a world where power is replacing law, and impunity is setting the pace.

18 January 2026

Best of 2025 - Gaza’s economy has collapsed beyond recognition

Gaza’s economy, society and basic infrastructure have been almost entirely wiped out. With 90 per cent of people displaced, food systems destroyed and schools and hospitals in ruins, reconstruction is becoming harder by the day.

16 January 2026

Banning slogans won’t build social cohesion

After Bondi, New South Wales politicians want to ban words and slogans. But rushed laws could punish political speech, not protect the public.

16 January 2026

Iran in the vortex: what's really happening

As protests unfold in Iran, Israeli and US figures openly talk of regime collapse. Foreign interference risks worsening violence and derailing change from within.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

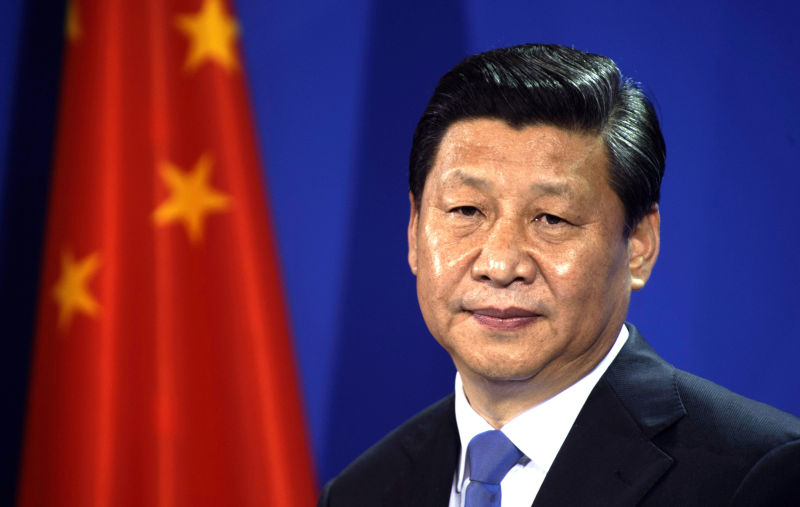

2 February 2026

Steadfast state support is key to China winning tech race with US

China’s sustained investment in science, engineering and technology is pulling it ahead globally, while the United States cuts research funding and hollow-outs its scientific workforce.

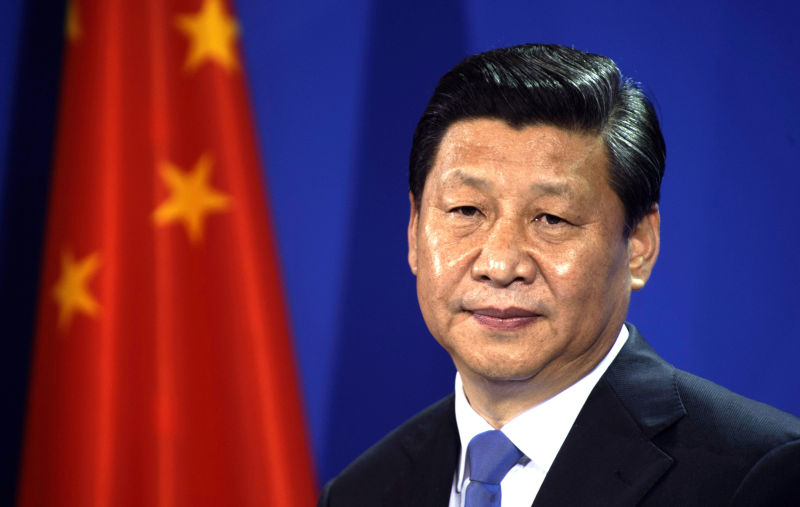

31 January 2026

Historic trade deal rejects Trump’s chaotic protectionism – Asian Media Report

The mother of all trade deals to America’s new defence strategy, the dismissal of a PLA princeling, Prabowo’s Peace Board support, ASEAN’s rejection of Myanmar junta’s poll victory and the deadly serious business of marriage in China – we present the latest news and views from our region.

31 January 2026

Historic trade deal rejects Trump’s chaotic protectionism – Asian Media Report

The mother of all trade deals to America’s new defence strategy, the dismissal of a PLA princeling, Prabowo’s Peace Board support, ASEAN’s rejection of Myanmar junta’s poll victory and the deadly serious business of marriage in China – we present the latest news and views from our region.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

The propaganda of American might

Ian Bowrey — Hamilton South

Tactical voting by Labor voters

John Small — Marrickville, NSW

But what about Pine Gap?

Penny Lee — Western Australia

Translation problems

Geoff Taylor — Borlu (Perth)