16 July 2025

Is Australia finally coming to terms with East Asia?

Comedy and economic development have one thing in common: timing is everything.

16 July 2025

Who's afraid of Donald Trump?

With his use of extreme tariffs to punish countries with trade surpluses, US President Donald Trump seems to be making an economic fool of himself.

16 July 2025

The Global South’s AI moment

If the Global South acts now, it can help build a future where algorithms bridge divides instead of deepening them – where they enable peace, not war.

Support our independent media

Pearls and Irritations is funded by our readers through flexible payment options. Choose to make a monthly or one off payment to support our informed commentary

Donate

16 July 2025

It’s time for another reforming and agitating attorney-general

Just last month Australia celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Whitlam Government’s Racial Discrimination Act (1975), without much fanfare it has to be said.

16 July 2025

The Israel lobby stands loudly condemned for its silence

Reflect for a moment, as you read this piece, what is happening in Gaza.

16 July 2025

What Australians think of Trump and the US

While the Murdoch media — and most of the pontificators writing op-eds for the rest of our news outlets — are having conniptions about whether and when Albanese might get a meeting with Trump, it comes at a time when the Australian public have little trust in the US and even less in Donald Trump.

16 July 2025

Systematic bias: how Western media reproduces the Israeli narrative

If words shape our consciousness, then the media holds the keys to minds.

16 July 2025

Humanity is ‘risking catastrophe’: UN

The full spread of the impending crisis facing humanity is, at long last, emerging into daylight with the publication by the United Nations of its 2025 Global Risks Report.

16 July 2025

More than 5,800 Gaza children diagnosed with malnutrition in June: UNICEF

Children's bodies are wasting away, the agency said. This is not just a nutrition crisis. It's a child survival emergency.

15 July 2025

Antisemitism in Australia: a 'pathology in our society'

There was much to read in the papers last Monday, the 7th of July. Three stories caught my attention.

15 July 2025

NYT report says Netanyahu prolonged war on Gaza to stay in power

He pressed ahead with the war in April and July 2024, even as top generals told him that there was no further military advantage to continuing, reports The New York Times.

Latest on Palestine and Israel

16 July 2025

The Israel lobby stands loudly condemned for its silence

Reflect for a moment, as you read this piece, what is happening in Gaza.

16 July 2025

Systematic bias: how Western media reproduces the Israeli narrative

If words shape our consciousness, then the media holds the keys to minds.

16 July 2025

More than 5,800 Gaza children diagnosed with malnutrition in June: UNICEF

Children's bodies are wasting away, the agency said. This is not just a nutrition crisis. It's a child survival emergency.

15 July 2025

NYT report says Netanyahu prolonged war on Gaza to stay in power

He pressed ahead with the war in April and July 2024, even as top generals told him that there was no further military advantage to continuing, reports The New York Times.

15 July 2025

Australian parliamentarians urgently need lessons in international law

As the new Parliament returns this month, it is timely to ask just how many Australian parliamentarians need urgent instruction in international law and how it impacts on government decision-making which complies with the United Nations rules-based order developed by the efforts of so many nations since 1945.

15 July 2025

'No' to Jillian Segal's antisemitism action plan

Representing Jews Against the Occupation ’48 (JAO48), I would like to share our response to Jillian Segal’s “antisemitism action plan”. In short: we reject it.

14 July 2025

Antisemitism Plan sparks fierce debate over free speech, racism, and political agendas

At a press conference in Sydney on Wednesday 10 July 2025, the Special Envoy to combat antisemitism, Jillian Segal, together with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke launched the National Action Plan to Combat Antisemitism in order to address antisemitic hate, especially in the wake of intensified community tensions following the war in Gaza.

13 July 2025

Kostakidis to go before court, after judiciary recognises anti-Zionism is not antisemitism

Mary Kostakidis should hold her head up high right now, because of all the Australian journalists who are honestly calling out the holocaust that Israel is perpetrating against the Palestinians.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

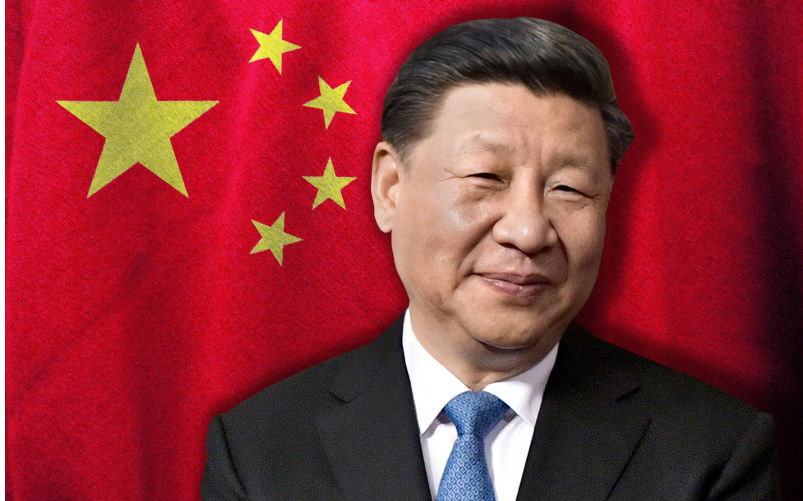

12 July 2025

Albanese’s visit to China is a moment for statesmanship

Membership of the Chinese Communist Party has just exceeded 100 million. It has long been the largest political party in world history.

12 July 2025

Albanese’s China mission – managing a complex relationship in a world of shifting alliances

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese leaves for China on Saturday, confident most Australians back the government’s handling of relations with our most important economic partner and the leading strategic power in Asia.

12 July 2025

US, China and Australia – an open letter to the PM

Dear PM Albanese, on Monday 30 June, the Chinese Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, had a letter published in The Australian entitled China and Australia are friends, not foes. This should never have been in question. It’s best to read the full version on China’s Embassy website.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Segal's imports

Steve M — Brisbane, QLD

Neither antisemitic nor anti-Jewish

Hal Duell — Alice Springs

The correspondence has been retained, Margaret

Geoff Taylor — Borlu

Renewable foods offer survival and peace

Chris Young — Surrey Hills, Vic