Pearlcasts

As we review 2025, the temptation is to look for neat summaries and settled conclusions.

Go to Pearlcasts

28 February 2026

From Whitlam to Andrew – the Palace and the politics of concealment

Allegations of royal funding in Prince Andrew’s settlement revive deeper questions about the monarchy’s political conduct – from the dismissal of Gough Whitlam to claims of concealed influence and broken trust.

28 February 2026

Message from the Editor

I tried very hard to comply with former US Labor Secretary Robert Reich’s call to boycott The US President’s State of the Union address this past week – but when the Al Jazeera prompt flashed up on my computer screen I caved.

28 February 2026

Modi in Israel, Tokyo’s shift on arms, and Duterte at The Hague – Asian Media Report

India and Israel deepen ties, Japan edges towards lethal arms exports, Duterte faces crimes-against-humanity charges, Indonesia weighs its Gaza role, Bangladesh confronts rule-of-law reform, and China’s unofficial K-pop ban shows signs of strain.

28 February 2026

From Iraq to Iran – how international law has unravelled

In 2003, governments at least felt compelled to argue the legality of war. In 2026, a possible strike on Iran proceeds without even the pretence of legal justification.

28 February 2026

Difficult women, comfortable power

When women refuse to soften their demands on violence, inequality and unpaid labour, the response is often to question their temperament rather than the broken system they are challenging.

28 February 2026

Punishment politics and the suppression of restorative justice

Decades of 'tough on crime' policy have expanded prisons while narrowing reform. Restorative justice has been repeatedly constrained not for lack of evidence, but because it redistributes authority away from the state.

28 February 2026

‘Arsonist as Fire Chief’: Fed appoints Wall Street lobbyist to key bank oversight role

The Federal Reserve has appointed longtime Wall Street lawyer Randall Guynn as its new director of supervision and regulation – a move critics say risks entrenching industry influence at the heart of financial oversight.

27 February 2026

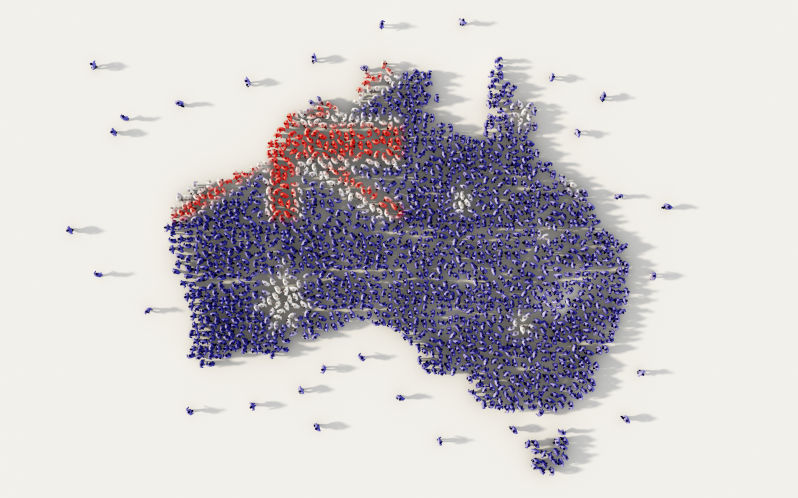

Authority is not leadership – and Australia keeps confusing the two

Australia’s political culture mistakes authority, comfort and continuity for leadership. Without the courage to create disequilibrium and confront hard choices, real reform remains impossible.

27 February 2026

Shen Yun and Falun Gong – belief, propaganda and division

The evacuation of the Prime Minister over a threat linked to a Shen Yun tour has drawn attention to the Falun Gong movement and its political evolution.

27 February 2026

What it means to belong as a Muslim Australian

A life shaped by migration, public service and community leadership offers a quiet rebuttal to claims that Muslim Australians do not belong – and a reminder that belonging is built through contribution, not fear.

27 February 2026

Pax Americana and the starvation siege of Cuba

For more than three decades the world has voted overwhelmingly to end the US embargo on Cuba. Washington ignores the law, the UN, and the humanitarian cost – and its allies look away.

Read our series

Latest on Palestine and Israel

27 February 2026

No Plan B: Trump’s Gaza plan sidelines justice and law

Donald Trump’s so-called Peace Board for Gaza promises reconstruction but delivers domination. With Palestinians excluded and international law sidelined, the plan exposes the urgent need for a credible alternative grounded in justice, accountability and self-determination.

26 February 2026

Foreign fighters for Israel – beyond the reach of Australian law?

While the government vows to block the return of Australian women and children from Syria, hundreds of Australians who have served with the Israeli Defence Force face little scrutiny on their return – despite serious allegations of war crimes in Gaza.

25 February 2026

Terrorism – a blow back from western violence in Muslim countries

Terrorism dominates political debate and media coverage in Australia despite causing relatively few deaths. The deeper causes – western military violence, state power, and selective moral language – are rarely examined.

24 February 2026

Death tolls, settlements and the closing space for a two-state future

New research confirms that far more Palestinians have been killed in Gaza than first acknowledged, while settlement expansion and political rhetoric point to deeper structural realities.

23 February 2026

Globalisation of occupation: when genocide becomes an international project

Thousands of foreign nationals are serving in Israel’s military with the legal tolerance of their home states, while peaceful protest against the war is criminalised. This double standard exposes a deep failure of international law and accountability.

23 February 2026

Islamophobia and strategic blindness: Australia in the Asian century

Australia seeks deeper integration with Asia while continuing to send cultural and political signals that undermine trust among its closest neighbours. In a region shaped by Islam, history and proximity, this contradiction carries strategic consequences.

21 February 2026

Board of Peace plans 5,000-person military base in southern Gaza

Leaked contracting documents detail plans by the Board of Peace to build a large military base in southern Gaza, including armoured towers, bunkers and a “Human Remains Protocol”.

20 February 2026

Dual nationals in Israel’s military face growing legal scrutiny over Gaza

Newly released data shows that tens of thousands of Israeli soldiers hold foreign citizenship, placing Western nationals directly within the scope of international war crimes law over Gaza.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

28 February 2026

Modi in Israel, Tokyo’s shift on arms, and Duterte at The Hague – Asian Media Report

India and Israel deepen ties, Japan edges towards lethal arms exports, Duterte faces crimes-against-humanity charges, Indonesia weighs its Gaza role, Bangladesh confronts rule-of-law reform, and China’s unofficial K-pop ban shows signs of strain.

27 February 2026

Shen Yun and Falun Gong – belief, propaganda and division

The evacuation of the Prime Minister over a threat linked to a Shen Yun tour has drawn attention to the Falun Gong movement and its political evolution.

25 February 2026

How a nuclear test that never happened became news

A US allegation that China conducted a secret nuclear test was widely reported despite clear evidence to the contrary, highlighting how security claims are too often treated as facts before they are proven.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

Hansonites are amongst us and they vote

Richard Llewellyn — Colo Vale

Assertions are not evidence of a crime

David Thompson — CLAYTON

Do some mothers matter more than others?

Hal Duell — Alice Springs

What’s the difference?

Stelios Piakis — NSW