Pearlcasts

As we review 2025, the temptation is to look for neat summaries and settled conclusions.

Go to Pearlcasts

4 February 2026

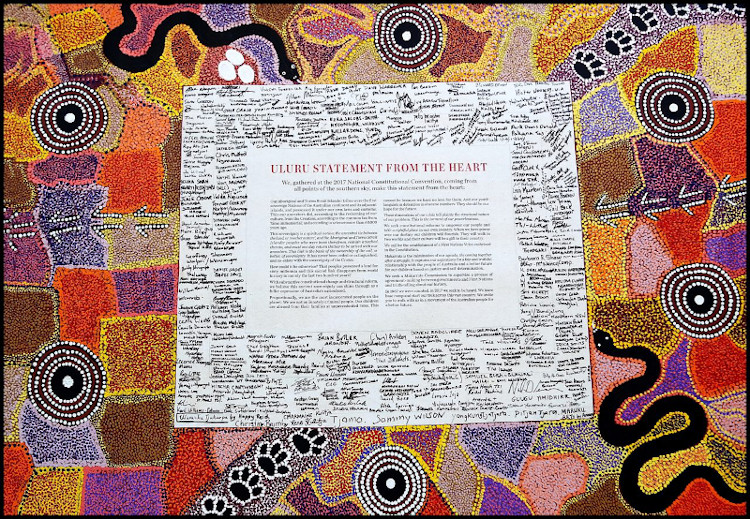

Australia's middle power diplomacy matters

Middle powers may lack the economic and military weight to coerce others, but they can still shape outcomes through coalition-building, credibility and sustained diplomatic effort.

4 February 2026

Abbott, Boyce and Trump – three ways to deny a warming world

Prominent political figures continue to dismiss or distort the evidence on climate change. Their claims collapse under even basic scrutiny, revealing resistance rooted not in science but in ideology and self-interest.

4 February 2026

AUKUS from where we are – and why that’s the problem

Australia’s AUKUS submarine program is tied to struggling US and UK shipbuilding systems, escalating costs and political whim, raising questions about whether the right defence choices were ever properly debated.

4 February 2026

Allegations, immunity, and a test of character

Australia’s migration law allows entry to be refused on character grounds including genocide, war crimes and incitement. How that discretion is exercised speaks directly to Australia’s commitment to international law.

4 February 2026

The smouldering wreckage on Capital Hill – part 2

The Liberal Party faces a structural dilemma – it cannot govern without the Nationals, yet governing with them pushes it further from the voters it needs. As support for the major parties erodes, Australia is edging towards a more fragmented political future.

4 February 2026

Education savings plans and the quiet erosion of public schooling

Education savings schemes appear sensible and responsible. But their quiet rise reflects a deeper failure – a loss of confidence in Australia’s commitment to properly fund public education as a shared civic good.

4 February 2026

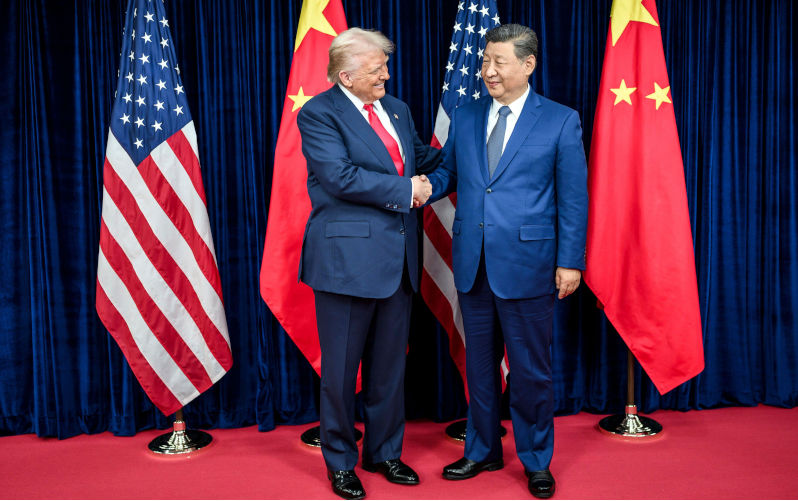

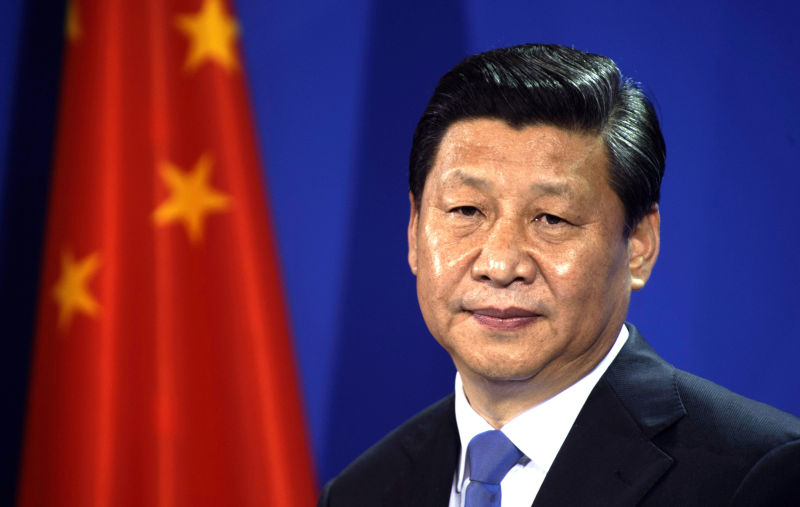

China pushes ahead in 2026 as Trump plays catch-up

China entered Donald Trump’s second presidency wary but prepared. Experience has taught Beijing to expect volatility, but also negotiation, shaping a strategy of caution, leverage and long-term planning.

4 February 2026

Israel and the return of settler politics in a lawless international system

Zionism emerged at the height of European settler colonialism and was realised just as the world turned toward decolonisation. Today, as international law loses force, Israel’s actions are again enabled by the prevailing global order.

4 February 2026

Trump, Afghanistan and the songs that tell a different story

Donald Trump should have listened to Australian songwriter Fred Smith before he spoke ignorantly about the sacrifices of soldiers in Afghanistan.

3 February 2026

Making polluters pay could fix Australia’s climate problem – and its budget

A new report shows how making polluters pay will not only diminish the threat from climate change, but it can also help restore the budget and the economy.

3 February 2026

The smouldering wreckage on Capital Hill – part 1

The Coalition’s implosion after the Bondi sitting was not a sudden accident. It exposed long-running tensions between the Liberals and Nationals, intensified by polling anxiety, One Nation’s rise and the limits of Australia’s Westminster conventions.

Read our series

Latest on Palestine and Israel

4 February 2026

Allegations, immunity, and a test of character

Australia’s migration law allows entry to be refused on character grounds including genocide, war crimes and incitement. How that discretion is exercised speaks directly to Australia’s commitment to international law.

4 February 2026

Israel and the return of settler politics in a lawless international system

Zionism emerged at the height of European settler colonialism and was realised just as the world turned toward decolonisation. Today, as international law loses force, Israel’s actions are again enabled by the prevailing global order.

29 January 2026

A war without headlines

The annihilation of Gaza has rendered the violence in the West Bank seemingly secondary in the global imagination.

26 January 2026

From international law to loyalty and deals: Trump’s Board of Peace play

The Trump-led Board of Peace points to a shift away from international law and multilateral institutions toward a system built on loyalty, coercion and financial leverage.

24 January 2026

Cultural “cohesion” becomes censorship, and a festival falls apart

Adelaide Writer’s Week was derailed after the withdrawal of an invited speaker, triggering mass author withdrawals and a board resignation. The episode raises hard questions about free speech, institutional courage, and the politics of Israel and Gaza in Australia’s cultural life.

23 January 2026

Bad laws are the worst sort of tyranny – and this one ticks every box

A sweeping new bill to combat antisemitism, hate and extremism was rushed through federal parliament this week with minimal scrutiny and major rule-of-law flaws. Its vague definitions, retrospective reach and expanded executive powers risk undermining rights, due process and democratic accountability.

20 January 2026

The rules are breaking – and the world is watching

The abduction of Venezuela’s president signals a world where power is replacing law, and impunity is setting the pace.

18 January 2026

Best of 2025 - Gaza’s economy has collapsed beyond recognition

Gaza’s economy, society and basic infrastructure have been almost entirely wiped out. With 90 per cent of people displaced, food systems destroyed and schools and hospitals in ruins, reconstruction is becoming harder by the day.

Israel's war against Gaza

Media coverage of the war in Gaza since October 2023 has spread a series of lies propagated by Israel and the United States. This publication presents information, analysis, clarification, views and perspectives largely unavailable in mainstream media in Australia and elsewhere.

Download the PDFLatest on China

4 February 2026

China pushes ahead in 2026 as Trump plays catch-up

China entered Donald Trump’s second presidency wary but prepared. Experience has taught Beijing to expect volatility, but also negotiation, shaping a strategy of caution, leverage and long-term planning.

2 February 2026

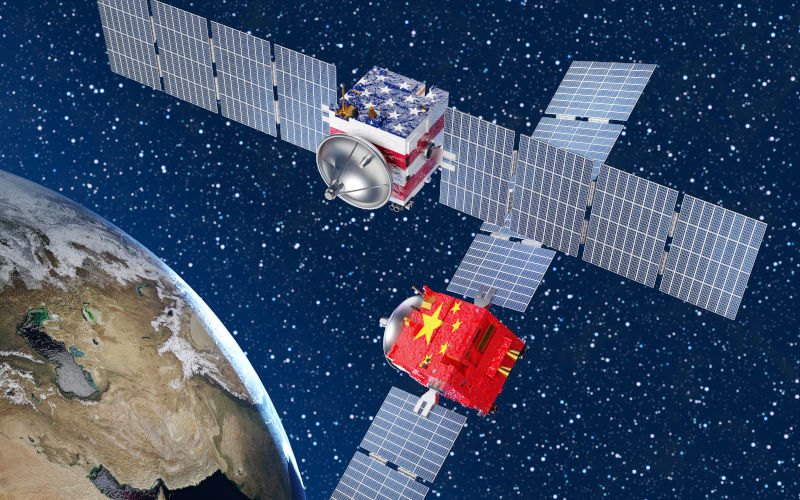

Steadfast state support is key to China winning tech race with US

China’s sustained investment in science, engineering and technology is pulling it ahead globally, while the United States cuts research funding and hollow-outs its scientific workforce.

31 January 2026

Historic trade deal rejects Trump’s chaotic protectionism – Asian Media Report

The mother of all trade deals to America’s new defence strategy, the dismissal of a PLA princeling, Prabowo’s Peace Board support, ASEAN’s rejection of Myanmar junta’s poll victory and the deadly serious business of marriage in China – we present the latest news and views from our region.

Support our independent media with your donation

Pearls and Irritations leads the way in raising and analysing vital issues often neglected in mainstream media. Your contribution supports our independence and quality commentary on matters importance to Australia and our region.

DonateMore from Pearls and Irritations

Latest letters to the editor

The propaganda of American might

Ian Bowrey — Hamilton South

Tactical voting by Labor voters

John Small — Marrickville, NSW

But what about Pine Gap?

Penny Lee — Western Australia

Translation problems

Geoff Taylor — Borlu (Perth)